“If liberty and equality, as is thought by some, are chiefly to be found in democracy, they will be attained when all persons alike share in the government to the utmost.”

~Aristotle, Politics

Following the first democratic, multiparty elections held in the Maldives in 2008, the change of power was perceived as the end of an era and heralding a new one. People from all walks of life, young and old, had united and rallied persistently for democratic reform, and succeeded. Hailed as a remarkable feat of people power, the Maldives was seen as a success story in nonviolent transition to democracy with much potential and promise.

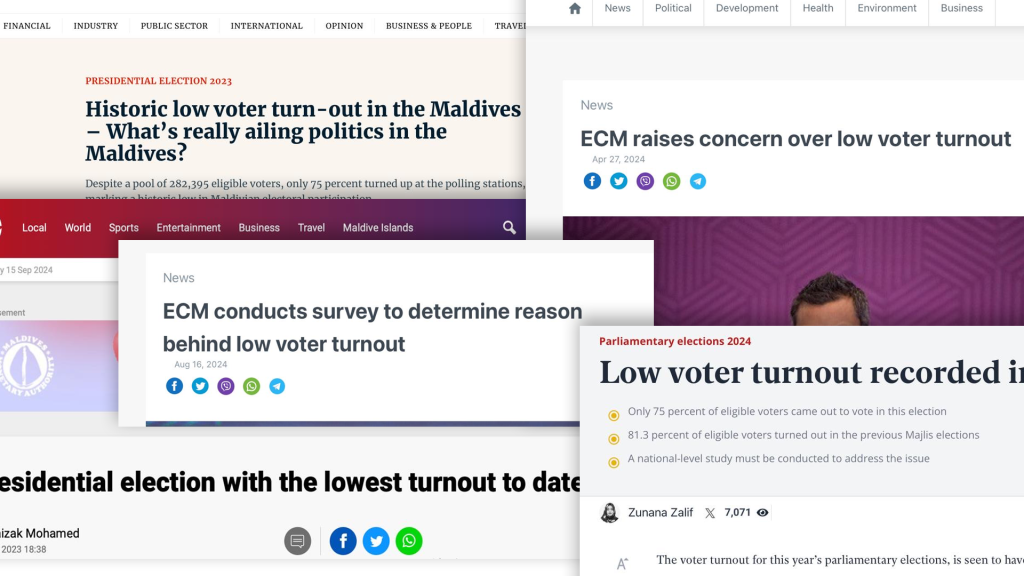

Sixteen years on, the picture has changed drastically and the political landscape is murky. There is growing dissatisfaction, mistrust and apathy of the general populace, and a striking distancing of everyday people from governance and political processes.

This brief examines reasons for discontent that result in apathy, the dangers posed by decreased and deteriorating civic involvement to democracy, and in light of the Maldivian context, some measures that can be taken to address common reasons for public frustration and encourage a more engaged citizenry.

Reasons for Discontent

Numerous rationales could be presented for the frustration and lack of faith of the public regarding political leaders, political parties and aspects of governance. Economic exclusion and widening disparity are considered key reasons for discontent, especially for the grievances of young people. According to the National Democratic Institute (NDI), “For many young people, their frustrations lie with poorly functioning governing institutions that aren’t delivering policies that meet their economic needs or align with their social values”[1]. Even in a small island nation as the Maldives, the effects of unprecedented economic inequality are felt profoundly. Research conducted by the SNF Agora Institute at the John Hopkins University and the International Republican Institute (IRI), found that despite challenges varying over different context, young people especially expressed increasing frustration with “growing economic and social inequality, lack of access to quality education, inaction on issues like climate change and environmental degradation, and aging governmental leaders who often do not effectively represent the issues they care about”[2]. The study highlighted though, the importance of distinguishing whether this frustration was towards the system of governance they were experiencing, which might claim to be democratic solely by name, or the very concept of democracy itself, and is a valid point to consider in analyzing reasons for apathy in the Maldives[3].

Dissatisfaction aimed at actors in governance and political spheres being aired on various platforms is not unique to the Maldives. There is growing frustration, and hence apathy, worldwide, primarily stemming from the reasons cited prior. The Centre for the Future of Democracy at the Bennett Institute for Public Policy, Cambridge, utilized the largest-ever dataset of democratic legitimacy to conclude that “young people’s faith in democratic politics is lower than any other age group and millennials across the world are more disillusioned with democracy than Generation X or baby boomers were at the same age”[4]. The study combined data of over 4.8 million respondents, 43 sources and 160 countries between 1973 and 2020, to analyze how satisfaction with democracy has changed over time among four generations[5]. It found that in developed and the most populous democracies, rising inequality and youth unemployment contributed greatly to a ‘democratic disconnect’, while in transitional or emerging democracies, there was a high level of initial satisfaction which over time deteriorated due to various factors[6].

Democracy in decline or poor governance?

One of the possible reasons for democratic disconnect explained as ‘transition fatigue’, could be of relevance and applicable to the Maldives as well. The study notes that youth disengagement from democracy may be related to the democratic transition process itself, with the memory of the struggle for democracy fading, and the coming to age of a new generation “that is less concerned with the value of democracy but as an ideal, and more concerned with itsfunctioning in practice – including the ability to address problems of youth unemployment, corruption, inequality and crime. Increasingly, the legitimacy of democracy therefore hinges on its performance – or failure – to face these mounting social challenges. Where this balance falls short, satisfaction with democracy declines”[7]. The study also notes that while older people who lived through the struggles for democracy were more likely to perceive democratic institutions more positively and remained as members of political parties, younger citizens “have grown up only in the shadow of democracy’s shortcomings”[8]. The Maldives appears to be a prime example of such dissatisfaction spurred on not because the populace disagrees with the idea of democracy, but for how it has performed and shortcomings in protecting the interests of the everyday person.

On this track, we can confidently assume it is not hostility towards democratic institutions but rather forms of inefficient and ineffective governance that has led to the growing ‘democratic disconnect’. However, this disappointment appears to be curtailing democracies worldwide. According to the Varieties of Democracy Institute (V-Dem), the global trend is veering away from democracy with 42 countries in the process of becoming autocracies, up from 33 last year, while only 14 countries are in the process of democratization[9]. V-Dem’s first Annual Report ‘Democracy at Dusk?’ published in 2017 highlighted that despite alarming signs it was not yet time to toll the death knell for democracy, noting that the normative power of democracy remained strong[10]. In its most recent Democracy Report of 2024, however, V-Dem noted again, autocratization continues to be the dominant trend[11]. The fact that young people are being increasingly swayed by populist politics of ‘strong man’ leaders or towards autocratic forms of governance is a matter for vigilance and thoughtful consideration.

Growing discontent and regressing democracy stemming from ‘bad governance’ can be the result of increase in corruption, failure to fulfill campaign and election pledges, and overall incompetence which lead to erosion of faith and trust in the system. Shana Mavee highlights governments being unresponsive to people’s needs, poor service delivery, corruption, inequality, among others as driving forces driving the public towards apathy[12]. In addition to issues related to governance, she also alludes to reasons social scientists have posed as explanations for civic apathy; perceiving political involvement as potentially detrimental to business interests, friendships and even family relations[13].

In the Maldives, popular and reiterated sentiment on social media point towards erosion in trust and loss of faith in the political system and ‘party politics’, governance and state institutions, as well as their capacity or willingness to work for reform or betterment of society. With escalating skepticism regarding governance and political actors, and perception of politically active peers as driven by selfish intent or as ‘duped’ by unscrupulous politicians with dubious agendas, there is consequent apathy and disenfranchisement as seen in young people’s shunning of activism and civic engagement.

In the Maldivian context, many who had previously been engaged and active in the spheres of governance and civil society point towards injustice and lack of accountability as reasons for disconnect and apathy. They allude to gross injustice, both scaling from state level issues to matters of everyday individuals where miscarriage of justice has eroded confidence in the judiciary.

Apathy’s aftermath

Democracy is not solely casting ballots or conducting regular elections with multiple candidates. In its essence, it embodies the rule of the people. In a system structured on the basis of upholding the will of the people, the people cannot be separate and far removed from the sphere of governance.

Writing for the Fair Observer, Scott Bennett notes our reaction to ‘political powerlessness’ is both emotional and rational; the emotional response manifesting as cynicism and the rational response as apathy[14]. He concludes that while cynicism is expected and individual apathy might appear to be logical, on a mass scale they can be disastrous[15].

Disastrous would be the apt expression. Civic apathy is witnessed when citizens exhibit disaffection and disenfranchisement from activities affecting the community or country, and possess no interest in contributing or engaging in such matters. The National Academy of Public Administration’s report ‘Strengthening democracy through citizen engagement’ focuses on some of the issues that arise when the public become disengaged, noting “If citizens do not get involved with the government, the crises will get much worse than they already are…The mistake is seriously compounded when citizens sit on the sidelines as cynics and critics, forgetting that in a democracy we are the primary office holders of government”[16].

Civic engagement plays an integral role in ensuring the robustness and vitality of democracy, and enabling democratic institutions to thrive and flourish as envisaged. It is a crucial pillar that promotes government’s accountability and transparency, especially with regards to access to information, whistle blower and media protection, and monitoring and oversight. Through civic engagement, individuals and communities are empowered to draw attention to their concerns and needs, and help direct resources to address those issues in the most effective and impactful manner. It also provides marginalized and vulnerable groups avenues for advocacy, inclusion and representation.

The people having a say in driving policy reform, in deciding what works and what doesn’t for their communities, in ensuring that power is not abused or exploited by those in positions of authority, is the hallmark of a healthy democracy. Civic apathy would lead to none other than decay and deterioration of democratic society. The adverse effect on local governance, in particular, will be debilitating as the entire system relies on empowering and engaging with the community in decision making. Lack of civic engagement is also one of the driving factors that enable impunity and hinder accountability. Authorities without the need for accountability are more likely to misappropriate and misuse funds and resources, and reinforce discriminatory policies[17]. The poorer the check on power, the greater the possibility of curbing civic engagement as well, resulting in a vicious cycle.

Regaining democracy – winning back the people

Democracy’s challenge appears to be combating citizen discontent and frustration which result in disinterest and apathy. Apathy leads to disassociation and disengagement. Any strides towards regaining lost ground and favor will have to prioritize winning back trust and confidence of the people. What can be done to encourage a more engaged citizenry, and thus more participatory democracy?

- Greater emphasis on civic education, to encourage embracing civic responsibility and equip with the tools and skills required to participate in policy making debate and discourse from a young age.Through realistic civic education, young people will also come to see democracy is not itself utopia, and will make accommodations for its shortcomings without falling in to cynicism and apathy[18]. While recent Maldivian governments have made attempts to incorporate civic education components to the school curriculum, there is a need for many more trained educators specializing in civic education’s formal instruction and informal curriculum. UNDP Maldives highlighted the Maldives has faced challenges in the delivery of civic education and actualization of holistic civic engagement, and given lack of resources, engagement of educators across the country has been challenging to sustain[19].

- The parliament adopting avenues and practices for consistent dialogue and consultation via community discussions and forums. Best practices exercised in other countries could be replicated and adopted to garner greater engagement and foster a better sense of ownership and individual responsibility among citizens regarding legislation. With a super majority of the executive in the Majlis, it is paramount to instill confidence in the legislative body’s sincerity in acting independently to protect the people’s interests, and not as an extension that will rubberstamp the government’s will.

- Stronger measures to curb corruption by all state institutions, and promoting open government and practicing a culture of openness with regards to transparency and accessibility to information. This can be aided by effective implementation of the Right to Information Act and Whistleblower Protection Act, and providing the space and resources for oversight bodies to function independently. IRI’s survey shows Maldivians rank corruption as the most significant problem in the country, and disaggregated data shows youth make up the majority of respondents who hold this view[20].

- Enabling an open and pluralistic civic space especially for CSOs and NGOs to explore their areas of interest and cooperating in their efforts. A dynamic and thriving civil society is important because they are often the first actors to be targeted when rule of law and democracy deteriorate, and the quality of civic space can be an indicator of the state of rule of law and democracy[21].

- Improving the social and economic wellbeing of young people through sound policy. Disenfranchisement of the youth cannot be dealt with without addressing the main reasons for discontent – economic exclusion and inequality. UNDP Maldives notes the mismatch between education opportunities and employment offerings have resulted in a quarter of youth being unemployed and consequently a large number of young individuals harbor deep disillusionment with public institutions and policy making processes[22]. Concerted effort must be made to further facilitate economic and income generating opportunities for young people, and to incorporate young people’s aspirations and feedback in formulating relevant programs and policies. Effort must also be made to provide them platforms for dialogue and discussion for continued engagement.

- Ensuring authentic public participation and contribution. IRI’s 2023 survey found that the majority of responders felt it was very unlikely for ordinary people to influence decisions made in the country[23]. When asked why community consultations conducted by local councils recorded dismally low attendance in most islands, both residents and councils often responded the people felt they possessed no real say and their contribution will not have any impact in a meaningful way. Public consultation should result in impact, and authorities must be clear in communicating actions taken following recommendations of such consultations. Consultations are a part of a process of engagement that should be ongoing, and not an activity to garner popularity ahead of elections.

- Prioritizing a people centered approach in policy making. According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), open government is at the heart of people centric policy, prioritizing transparency, accessibility, integrity, responsiveness, equality and stakeholder participation, and for such a process to be effective, resistance to change must be overcome and working in silos in public administration must be abolished[24]. A model such as the Serving Citizens Scorecard Framework developed by OECD in 2017[25] could be adopted to gauge the public’s sentiment and satisfaction regarding various sectors on a regular basis. State apparatus must be structured around catering to the wellbeing and satisfying needs of the people equitably.

- Ensuring justice and accountability through all available state mechanisms. Injustice and lack of accountability are reason cited in the Maldives and worldwide for the citizens’ loss of trust and confidence in state institutions. In the absence of justice for all in equal measure, there is no validity of democracy. Lack of accountability results in continued violation of rights and impunity. Citizens’ feelings of helplessness and isolation enhance with every such failure, and reinforces the perception “some animals are more equal than others”. Timely, effective justice needs to be done, and must be seen to be done, through the entirety of the state apparatus to win back the public faith in a system they believe is gravely flawed and corrupted. Action must be taken against perpetrators of violations, and lessons learnt must be applied across the state machinery to ensure they do not keep repeating.

In conclusion, a state exists not for its people to remain on the periphery as detached, helpless onlookers but rather their wellbeing, security and growth are the reasons for the state’s existence.

[1] NDI, ‘Youth building the new democratic blueprint’, August 2024 https://www.ndi.org/our-stories/youth-building-new-democratic-blueprint

[2] SNF Agora Institute at John Hopkins University and IRI, ‘Understanding Youth Perceptions Towards Authoritarianism’, June 2024 https://snfagora.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/SNFReportDesign2YA_r655.pdf

[3] Ibid

[4] Bennett Institute for Public Policy, Cambridge, ‘Youth and satisfaction with democracy’, October 2020 https://www.bennettinstitute.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Youth_and_Satisfaction_with_Democracy-lite.pdf

[5] Ibid

[6] Ibid

[7] Ibid

[8] Bennett Institute for Public Policy, Cambridge, ‘Youth and satisfaction with democracy’, October 2020 https://www.bennettinstitute.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Youth_and_Satisfaction_with_Democracy-lite.pdf

[9] V-Dem Institute, ‘Democracy at Dusk? V-Dem Annual Report 2017’ https://v-dem.net/documents/18/dr_2017.pdf

[10] Ibid

[11] V-Dem Institute, ‘Democracy Report 2024’, https://v-dem.net/documents/43/v-dem_dr2024_lowres.pdf

[12] Mavee S., ‘A Conceptual Analysis of Civic Apathy in Democratic Governance’, 2015 https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/ejc-adminpub-v23-n2-a8

[13] Ibid

[14] Bennett S, Fair Observer, ‘Political apathy is rational, but don’t fall for it’, September 2023, https://www.fairobserver.com/world-news/political-apathy-is-rational-but-dont-fall-for-it/#

[15] Ibid

[16] The National Academy of Public Administration, ‘Strengthening democracy through citizen engagement’, July 2003 https://s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/napa-2021/studies/strengthening-democracy-through-citizen-engagement-insights-for-public-admi/03_07Civic_Engagement.pdf

[17] Fraser S., ‘Political apathy and how to reignite political engagement’ https://africandevelopmentchoices.org/political-apathy-and-how-to-reignite-political-engagement/

[18] Branson M.S., ‘The Role of Civic Education’, 1998 https://www.civiced.org/papers/articles_role.html

[19] UNDP Maldives, ‘The Significance of Civic Education in the Maldives: Nurturing Informed and Engaged Citizens’, August 2023

[20] Centre for Insights on Survey Research, IRI, ‘National Survey of Residents of the Republic of Maldives’, August – September 2023

[21] European Civic Forum, Civic Space Watch https://civicspacewatch.eu/what-is-civic-space/

[22] UNDP Maldives, ‘The Significance of Civic Education in the Maldives: Nurturing Informed and Engaged Citizens’, August 2023

[23] Centre for Insights on Survey Research, IRI, ‘National Survey of Residents of the Republic of Maldives’, August – September 2023

[24] OECD, Government at a Glance 2019, November 2019 https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/government-at-a-glance-2019_8ccf5c38-en

[25] Ibid