The Maldives – renowned for its turquoise seas and idyllic resorts – is also home to a youthful population grappling with stark realities beneath the postcard perfection. According to the 2022 Population and Housing Census, adolescents aged 10–19 comprise approximately 13.8% of the total population, representing more than 71,000 individuals (National Bureau of Statistics, 2023). This demographic cohort, situated at the intersection of childhood and adulthood, bears the weight of the country’s future aspirations. Yet, adolescence in the Maldives is increasingly marked by unspoken challenges. From domestic violence and school-based bullying to rising mental health concerns, engagement in risky behaviours, and educational disengagement, Maldivian adolescents are coming of age during a period of rapid socioeconomic change.

Family dynamics, shifting aspirations, and urbanization have introduced new vulnerabilities even as basic services like health and education reach near-universal levels. While the country has made remarkable progress in areas such as maternal and child health, complex adolescent-specific challenges—such as violence, substance use, psychological distress, and digital risks—are surfacing with growing urgency (UNICEF Maldives, 2023). This introductory article of a four-part series, written to mark the Maldives National Children’s Day on May 10, provides an overview of these intersecting issues and calls for a compassionate, data-driven response that places adolescents at the centre of national dialogue and policy planning.

The Great Divide: Struggling to Cross the Bridge to Upper Secondary Education

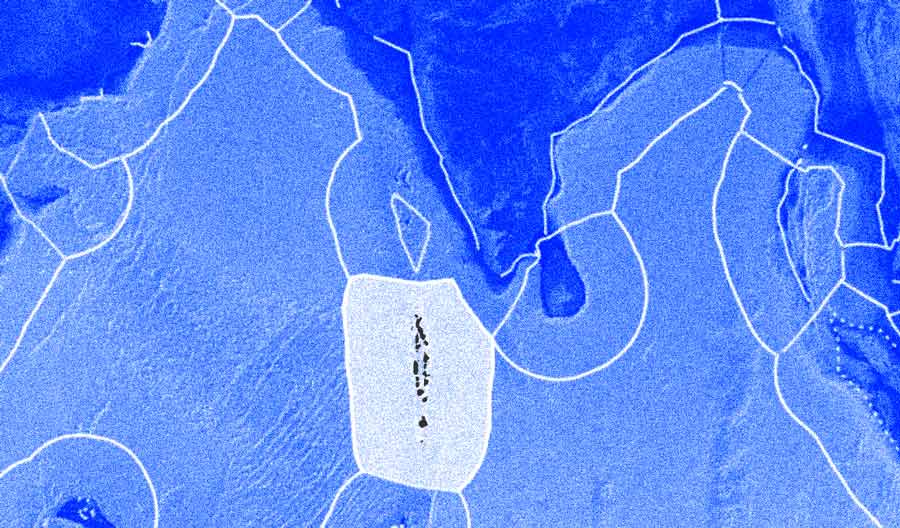

For Maldivian adolescents, one of the most critical junctures is the leap from basic schooling to higher education – a jump many are unable to make. Education in the Maldives is free and near-universal up to Grade 10 (lower secondary), and most adolescents complete their O-Level education. However, after age 16, the educational pipeline narrows dramatically. According to the 2022 Population and Housing Census, only 44.5% of adolescents enroll in higher secondary education (Grades 11–12), meaning more than half of Maldivian youth cease formal schooling by the end of lower secondary (National Bureau of Statistics, 2023). This steep drop-off is well below the average for upper-middle-income countries and represents a persistent “education gap.”

The reasons are structural and socio-economic. Outside Malé and a few urban centers, many islands lack higher secondary facilities, compelling students to either relocate or abandon further education altogether. This limited access has “restricted educational opportunities” for older children in remote atolls (National Bureau of Statistics, 2023). Economic constraints are also at play—some families cannot afford to support a non-working adolescent through two additional years of schooling without clear economic payoff.

A growing gender disparity is also evident. The 2022 Census shows that girls now slightly outnumber boys in higher secondary enrollment, reversing historical trends (National Bureau of Statistics, 2023). This suggests that boys are more likely to drop out after Grade 10, whether due to employment prospects, disengagement, or peer influences, while more girls persist through A-Levels.

The ramifications of this divide are profound. Youth who leave school at 16 face limited career pathways in an economy that increasingly demands higher-order skills. Recent policy efforts to recruit school dropouts into the military and security forces—though framed as an opportunity—raise complex questions about voluntariness, informed choice, and potential rights violations for minors at risk of disengagement. The government’s move to financially incentivize this recruitment further complicates matters, as it may result in minors being pressured into enlistment by families seeking income, eroding their sense of agency and long-term aspirations. Frustration from stalled aspirations can manifest in broader social issues, including crime, substance abuse, or disengagement.

Lost and Left Out: The Growing Epidemic of Youth Disengagement

Too many Maldivian adolescents today find themselves in a state of limbo – neither in school, nor employed, nor in training – drifting at the margins during what should be a formative period of growth. This youth disengagement is a pressing concern for a small country that needs every young citizen actively building skills. According to the 2022 Population and Housing Census, approximately 16% of Maldivians aged 15–17 were not in education, employment, or training (NEET), with boys slightly more likely than girls to fall into this category (National Bureau of Statistics, 2023). In other words, roughly one in six older adolescents is essentially idle.

This sense of idleness is compounded by a disconnect from national life. The Maldives National University’s 2022 public perception study revealed that many young people feel excluded from political and civic participation, frequently citing nepotism, corruption, and a lack of local avenues to engage as reasons for their disengagement (MNU, 2022). As elections become increasingly monetized, this exclusion becomes more corrosive. New voters, often young and economically vulnerable, are more susceptible to being influenced by short-term material incentives rather than long-term democratic ideals—undermining meaningful participation.

Family dysfunction and weak parental bonds further contribute to youth vulnerability. Adolescents from unstable homes often turn to peers for validation, which can lead to risky behaviours such as substance use or petty crime. Youth also pointed to the lack of mentoring, life skills, and reproductive health education as key gaps in their development (MNU, 2022).

Adding to the issue is the mismatch between education and labour market needs. School leavers often lack the networks or skills to access viable employment—especially in the atolls where jobs are scarce and often dominated by adult migrant workers. This disconnect fosters a state of “voluntary unemployment,” not due to apathy but due to limited meaningful opportunities (MNU, 2022; UNDP, 2019).

Perhaps most invisibly affected are adolescents who come into conflict with the law. In urban centres, they often vanish into anonymous isolation, while in small island communities, they face intense stigma and exclusion. With limited rehabilitation and reintegration pathways, many risk permanent marginalization unless brought back into the social fold with urgency and care.

The social cost of youth disengagement is high: not only is the nation’s human capital underutilized, but it also feeds broader risks of crime, addiction, and long-term marginalization.

A Diet of Disconnection: How Modern Lifestyles Are Harming Our Youth

Beyond acute crises, Maldivian adolescents also face a slow-burning threat to their long-term health. As lifestyles in the Maldives rapidly modernize, the habits formed during adolescence are fueling risks for non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and certain cancers. Traditional diets of fresh fish and coconut are increasingly being replaced by high-sugar beverages and ultra-processed foods. According to the WHO’s Global School-based Student Health Survey, nearly one in three Maldivian adolescents consume carbonated soft drinks at least once a day, and approximately 16% of school-going adolescents are now classified as overweight or obese (World Health Organization, 2020).

On the opposite end of the nutritional spectrum, a significant proportion of youth still struggle with undernutrition. According to national data, 16% of adolescent boys and 30% of adolescent girls are underweight, while 25% of boys and 21% of girls are overweight or obese. This dual burden of malnutrition underscores deep inequalities in dietary quality and access. In addition, 28% of boys and 45% of girls suffer from anemia, highlighting critical micronutrient deficiencies during adolescence. Concerningly, these health risks are being amplified by changing dietary habits: between 2009 and 2014, fast food consumption among adolescents more than doubled—from 16% to 36.7%—while daily carbonated drink consumption rose from 33% to 60%. These shifts suggest a generation increasingly exposed to poor nutritional habits. Compounding these risks is the rise in sedentary behaviours: according to the 2020 STEP Survey, over 80% of Maldivian adolescents aged 13–17 were not engaging in sufficient physical activity, implying that only one in five adolescents meets the minimum global recommendation for physical activity. As screen time displaces outdoor play and structured exercise, these lifestyle changes mark a worrying trajectory for adolescent health in the Maldives — one that could lead to long-term consequences in adulthood.

Adding to these concerns is the early initiation into harmful substances. About 12% of adolescents aged 13–17 report using some form of tobacco, while nearly 10% are regular cigarette smokers (World Health Organization, 2020). Though alcohol use remains low due to legal and cultural constraints, the misuse of substances such as inhalants and prescription drugs is an emerging threat.

Public health officials warn that the country is sitting on a “ticking time bomb” of adolescent lifestyle disease, as the Maldives already grapples with high adult prevalence of diabetes and hypertension. Without strategic intervention, today’s adolescents could face these chronic illnesses even earlier in life. Tackling this challenge requires early preventive action: enhancing nutrition in school canteens, strengthening health education into curricula, promoting sports and physical activity, and maintaining robust anti-tobacco and anti-drug campaigns. While these risks may not make headlines like violence or crime, they pose an equally grave threat to the long-term health and productivity of the nation’s youth.

The Quiet Emergency: Adolescent Mental Health in Decline

Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, data from the 2014 Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS) in the Maldives showed that over 13.1% of students aged 13–17 had seriously considered suicide, and approximately 12.6% had attempted suicide in the past year (Ministry of Health & WHO, 2014).

These alarming figures signal a deeper undercurrent of psychological distress. Academic pressure remains a leading stressor, cited frequently by both students and parents, compounded by minimal time for rest and recreation. Bullying—both offline and online—continues to erode adolescents’ self-worth, and the stigma surrounding mental illness contributes to an environment where emotional struggles are too often concealed, misunderstood and stigmatized. (UNICEF Maldives, 2023).

The COVID-19 pandemic only deepened this crisis. Lockdowns, loss of household income, and prolonged social isolation triggered what many adolescents described as “feelings of hopelessness and helplessness” (UNICEF Maldives, 2023). Despite the clear need, mental health services remain grossly inadequate. Until recently, there were no dedicated child psychologists in most atolls. While a central mental health center opened in Malé in 2019, community-based services tailored to children, adolescents and youth remain significantly limited.

Cultural taboos further inhibit care-seeking behaviour, deterring families from acknowledging or addressing adolescents’ mental health concerns. As a result, many young Maldivians continue to suffer in silence, their anxiety, depression, or trauma left unrecognized and untreated. Addressing this quiet emergency will require both normalizing mental health conversations, help seeking in early stages and scaling up access to adolescent-friendly psychological and psychiatric support services across the nation (UNICEF Maldives, 2023). Investing in prevention programmes and early detection and support is also critical to reduce the demand and burden on specialized mental health services.

Too Young for Handcuffs: Adolescents Trapped in a Punitive System

A growing wave of youth crime is testing the limits of the Maldives’ justice system. In the first half of 2019, 155 children — some as young as 13 — were apprehended for criminal offenses, with 95% of those arrested being boys (Maldives Police Service, 2019, as cited in UNICEF Maldives, 2023). Many of these offenses are tied to the country’s expanding drug trade and gang networks; a 2016 estimate suggested that there were approximately 7,500 drug users in Malé alone, over half aged 15–24 (National Drug Agency, 2016, as cited in UNICEF Maldives, 2023).

Gangs increasingly target and recruit disenfranchised boys, using them as couriers or lookouts, aware that children under a certain age are exempt from prosecution. Under current Maldivian law, the minimum age of criminal responsibility is 15 years. While this threshold aims to shield young children from harsh punitive measures, it has created legal gaps—especially for pre-teens involved in serious offenses. In a widely publicized incident, a viral video showed 12- and 13-year-olds brutally assaulting another child, sparking national outrage (Atoll Times, 2023). Authorities later revealed that around 200 children, mostly aged 12–14, were identified as requiring rehabilitation for violent or criminal behavior, yet they remain beyond the reach of legal accountability (Atoll Times, 2023).

Emerging behaviours further complicate this landscape. As reported by MV Plus Media (2025), gambling addiction is rising among adolescents, with many investing in cryptocurrencies and gambling through online platforms. These risky behaviours not only contribute to financial dependency and mental stress but are also reportedly linked to serious and organized crimes. Some adolescents are allegedly using earnings from gambling to fund drug purchases—no longer relying on family allowances. Others are becoming addicted to online gaming, while young adults are even taking loans to support their engagement in these behaviours. Such trends call for urgent regulatory scrutiny and the development of digital literacy and addiction prevention programs.

In response, the government has proposed lowering the age of criminal responsibility to 12 years from the current age of 15—a move that has triggered significant debate over children’s rights, developmental readiness, and the long-term consequences of criminalizing adolescence. Critics argue that such reforms may expose vulnerable children to the justice system prematurely, without offering adequate support structures.

Behind Closed Doors: Adolescents and the Hidden Crisis of Violence

In quiet islands and dense city neighborhoods alike, many adolescents live with threats that remain hidden behind closed doors. Violence against children and adolescents—including physical abuse, neglect, and sexual exploitation—remains distressingly common. In 2023, the Ministry of Gender, Family and Social Services recorded 889 cases of violence against children, with 489 involving girls and 400 involving boys. The majority of these cases involved neglect, followed by sexual and physical abuse. Sexual violence disproportionately affected girls — with approximately 80% of child sexual abuse cases involving female victims (Ministry of Gender, Family and Social Services, 2023; Maldives Bureau of Statistics, 2023). These trends are echoed in crime statistics from the Maldives Police Service, which recorded 136 cases of crimes against children in just the final quarter of 2023, reflecting an ongoing and serious national concern. Despite legal protections, the prevalence and persistence of child abuse in the Maldives underscores significant gaps in enforcement, early intervention, and support services. On average, approximately 40 cases of domestic or gender-based violence involving minors are reported monthly—a figure that surged during the COVID-19 pandemic as economic hardship intensified household stress (UNICEF Maldives, 2023).

The trauma isn’t confined to homes. Schools, meant to be safe spaces for learning and growth, are also settings where violence unfolds: about one in four Maldivian students aged 13–15 report having been bullied (World Health Organization, 2020). With the rise of digital platforms, adolescents face new risks such as cyberbullying and online grooming. During the pandemic lockdown alone, authorities documented 16 cyberbullying cases (UNICEF Maldives, 2023). The Maldives has also appeared on international watch lists for not meeting minimum standards in combating child trafficking (U.S. Department of State, 2022).

Despite existing legal protections, adolescents—especially girls—remain disproportionately vulnerable to sexual violence, often at the hands of trusted individuals within domestic spaces. The normalization of abuse, combined with weak enforcement and pervasive stigma, means many incidents go unreported. These sobering realities shatter the illusion of a carefree island childhood. Protecting young Maldivians demands urgent investment in robust child protection systems, stronger enforcement, and community-driven prevention efforts.

The challenges confronting Maldivian adolescents are not isolated problems but deeply interconnected threads — forming a web that entangles the future of a generation. Violence leaves invisible wounds that echo in mental health struggles. Untreated mental distress often leads to school dropout or disengagement, pushing young people toward crime, substance use, or digital addiction. Meanwhile, exclusion from education and alternative pathways to it narrows their life chances, deepens poverty, and fosters resentment. These are not parallel crises — they are mutually reinforcing.

This paper, released in commemoration of Children’s Day on May 10, marks the beginning of a four-part series that calls attention to these complex, often overlooked realities of adolescent life in the Maldives. In the weeks to come, we will take a closer look at the themes introduced here: crime and risky behaviors, mental health and lifestyle diseases, and the breakdown of educational pathways.

Because the future is not tomorrow. It’s already here — and it’s 13, 15, 17 years old. And it’s waiting.

References

Ali, R. (2024). Frozen, Tangled, Brave – Not a Disney Phenomenon: Childhood experiences of adult children who had a parent with a drug addiction [Master’s dissertation, University of Malta].

Amonath, S. (2015). Challenges that are faced by schools in implementing health education program [Bachelor’s dissertation, Maldives National University].

Bureau of Statistics. (2023). Education Status of the Population: An analysis from Census 2022. Ministry of National Planning, Housing & Infrastructure. Retrieved from https://statisticsmaldives.gov.mv

Gough, J. (2020). Voices of Youth: South Asian perspectives on education, skills and employment. UNICEF Regional Office for South Asia.

Haarr, R. (2023). Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Study on Parenting and Childcare in Maldives. UNICEF & Villa College.

Maldives National University. (2022). Disengagement of Maldivian Youth: A public perception study. Research Development Office.

Mental Health Directorate, Ministry of Health. (2025). National Mental Health Strategic Action Plan 2025–2029. Republic of Maldives.

Ministry of Gender, Family and Social Services. (2023). Monthly case statistics: Violence against children, 2023. Malé: Government of Maldives. Retrieved from https://www.gender.gov.mv

Maldives Bureau of Statistics. (2023). World Children’s Day 2023: Statistical Highlights. Malé: Government of Maldives. Retrieved from https://statisticsmaldives.gov.mv

Maldives Police Service. (2023). Quarterly Crime Statistics: Q4 2023. Malé: Maldives Police Service. Retrieved from https://www.police.gov.mv

Mudunna, C., Tran, T. D., Antoniades, J., & Chandradasa, M. (2025). Mental health of adolescents in countries of South-East Asia: A policy review. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2025.104386

Naseer, A. (2015). Prevalence and factors associated with self-mutilation among adolescents of Malé schools [Bachelor’s dissertation, Maldives National University].

Rapid Assessment Team. (2022). Rapid Assessment of Mental Health Awareness in the Republic of Maldives. National Mental Health Awareness Campaign.

UNICEF. (2023). Situation Analysis of Children and Women in the Maldives 2023. UNICEF Maldives.

World Health Organization. (2021). Global School-based Student Health Survey: Maldives Fact Sheet. Retrieved from https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/ncds/ncd-surveillance/gshs/maldives

World Health Organization. (2023). Adolescent nutrition data portal. Retrieved from https://cdn.who.int

MVPlus Media. (2025, May 7). Gambling addiction and crypto-linked crime rising among Maldivian adolescents, officials warn. MVPlus News. Retrieved from https://mvplusmedia.mv (hypothetical citation placeholder; update URL upon final publication)

Leave a Reply