Executive Summary

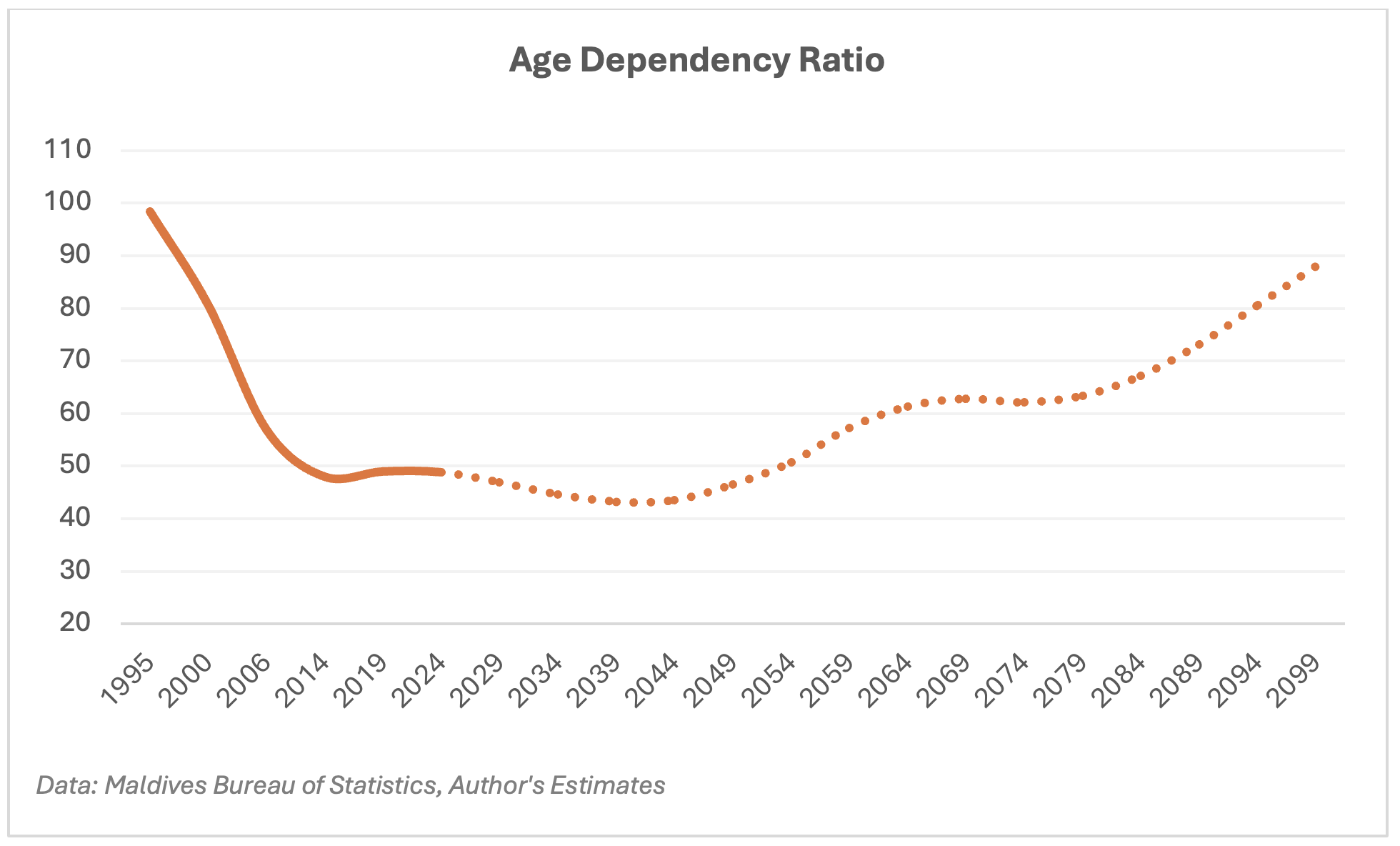

- Demographic dividend window: The Maldives now has a large working-age population relative to dependents, but this advantage will close by the 2050s–2060s as the country ages.

- Why it matters: Without reforms, aging could subtract 0.5–1 percentage point from annual growth, strain pensions and health systems, and increase fiscal and social risks.

- Lessons from Asia: Korea and Singapore turned their demographic windows into lasting prosperity by investing in education, productivity, and institutions.

- Policy priorities: Invest in human capital, reshape the state’s role, raise productivity and diversification, secure fiscal and social sustainability, embrace migration, and strengthen institutions.

- The choice is urgent: By 2064, the total dependency ratio could exceed 60 dependents per 100 workers. If the Maldives acts now, it can grow rich before growing old; if not, it risks stagnation and vulnerability as the population ages.

- 2025–2050 economic targets: By 2050, the Maldives should aim to double GDP per capita to at least USD 25,000 (PPP), sustain labour productivity growth of at least 2% a year, and build fiscal buffers of 10–15% of GDP. These targets will ensure resilience as the population ages.

Introduction

The Maldives stands at a historic turning point. For the first time in its history, the country enjoys a demographic dividend: a large working-age population relative to dependents. This window, however, is temporary. By the 2050s and 2060s, the Maldivian population will begin to age and eventually decline, with a shrinking workforce supporting a growing elderly population. The question is stark: can we build enough wealth and resilience now to sustain the economy later?

The lessons from Asia are clear. Korea and Singapore turned their demographic windfalls into enduring prosperity by investing in people, technology, and institutions. They became rich before they became old. The Maldives must follow this path—acting decisively while the window is open—to ensure that the coming demographic cliff does not derail its future.

Where We Are Today: The Maldivian Transition

The Maldives has experienced one of the most dramatic demographic transitions of any small state. Fertility has fallen from more than 7 births per woman in the early 1980s to just 1.7 births per woman in 2022—well below the replacement rate of 2. Mortality has also declined as access to health care improved and living standards rose. Life expectancy now exceeds 81 years, compared to around 60 just four decades ago.

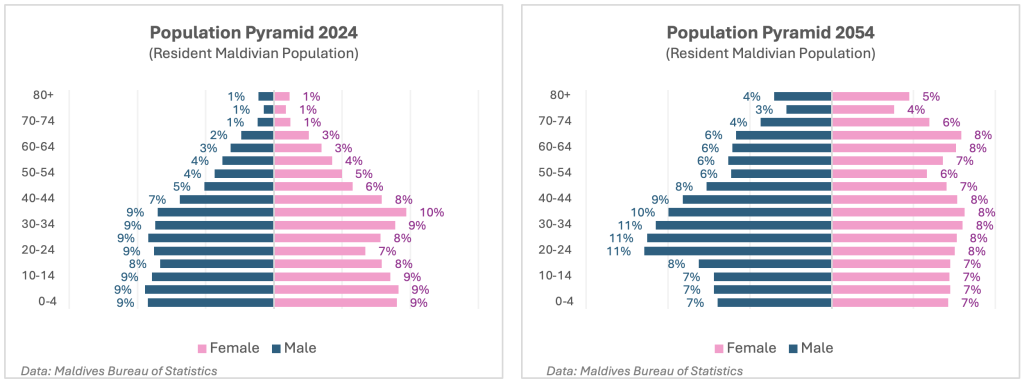

The result is a young and potentially energetic population. The 2024 population pyramid shows a broad base of working-age Maldivians, with more than 67 percent of the population between ages 15 and 64. The youth bulge is especially significant: over half of the workforce is under 30, meaning they could contribute economically for several decades if provided with skills and opportunities.

The dependency ratio—the number of dependents (under 15 and over 65) per 100 working-age adults—has been falling since the early 1990s. At its peak, there were over 90 dependents for every 100 workers. Today, the ratio is around 48, one of the lowest in the region. This is the essence of the demographic dividend: a period when each worker supports fewer dependents, freeing resources for savings, investment, and growth.

But this window is finite. Demographic projections suggest that by 2050 the share of the elderly population (65+) will more than double to over 14 percent. By 2060, the overall population is likely to plateau and begin declining, with the working-age share shrinking and the elderly share continuing to climb. The pyramid will invert, with fewer young workers at the base and many more elderly at the top. By 2064, the total dependency ratio could exceed 60 dependents per 100 workers. This would significantly raise the burden on the working-age population.

This creates both opportunity and urgency. The Maldives must accelerate productivity, savings, and economic diversification while its age structure is favourable. The clock is ticking, and the pyramid of 2054 reminds us that today’s advantage will not last.

Why This Window Matters

The demographic dividend is the potential economic boost that comes from a favourable age structure. When the majority of citizens are in their productive years, a country can enjoy faster growth, higher savings, and social dynamism. But the dividend is not guaranteed. Without the right investments, it can be squandered, leaving the country unprepared for the demographic headwinds that follow.

By mid-century, the picture will look very different. The share of Maldivians aged 65 and older will double, and the dependency ratio will rise again. Instead of many workers supporting a few dependents, fewer workers will support many retirees. This shift brings several risks:

- Economic drag: IMF studies show that aging can subtract 0.5–1 percentage point from annual GDP growth in post-dividend economies. Over decades, this compounds into much lower income levels.

- Fiscal stress: Aging societies face rising costs for pensions, health care, and elder support, even as the tax base shrinks. For the Maldives, where social protection is already limited, the challenge will be building sustainable systems before demand surges.

- Social risks: If young workers feel overburdened by supporting retirees, intergenerational tension can rise. At the same time, without adequate preparation, older Maldivians risk poverty and exclusion.

- Macroeconomic vulnerability: A smaller workforce may also mean less capacity to adapt to climate change, diversify the economy, or sustain tourism-driven foreign exchange.

Japan offers a cautionary example. Once a rapidly growing economy, its aging population has depressed growth, weakened productivity, and constrained fiscal and monetary space. Unlike Japan, the Maldives does not have the cushion of decades of accumulated wealth. If the window is missed, the country could face slow growth and fiscal stress precisely when it needs resources to care for an older society.

That is why the current demographic dividend must be treated as a one-time development gift. Concretely, that means setting—and meeting—economic targets: GDP per capita to at least USD 25,000 (PPP) by 2050, labour productivity growth at least 2% a year, and fiscal savings of 10–15% of GDP by mid-century to finance rising pension and health costs.

Properly harnessed, it can lift GDP per capita to levels high enough to sustain growth and social protection into the aging years. Wasted, it will leave the Maldives facing its demographic cliff without a safety net.

Lessons from Korea and Singapore

The economic miracles of Korea and Singapore did not happen by chance. Both countries experienced fertility declines and a bulge of working-age citizens. They seized the opportunity with decisive policies:

- Education and skills: Massive investments in schooling and vocational training ensured that the young workforce was highly productive.

- Export orientation: Both countries integrated aggressively into global trade, creating jobs and building industries.

- High savings and investment: Fiscal prudence and strong financial systems turned household savings into capital for infrastructure and business.

- Institutions: Rule of law, capable bureaucracies, and strategic planning underpinned long-term development.

Today, both countries are aging, but they are aging rich. Korea is already post-dividend, and Singapore will fully transition around 2030. Their experience underscores the importance of using the dividend years wisely. The Maldives need not copy their population structure, but it must emulate their playbook: prioritize productivity, skills, openness, and institutional quality. Their success underscores that demographics create potential, but policy determines outcomes.

The Demographic Cliff Ahead

Asia is aging faster than Europe or the United States. While Europe took 50 years to move from young to old, many Asian nations are completing the same transition in just 20–25 years. That means far less time to adapt.

For countries already past their dividend, demographics subtract between 0.5 and 1 percentage point from annual GDP growth. Immigration and productivity gains can soften the blow, but they cannot reverse it. For the Maldives, the cliff is visible: a steadily rising share of elderly, a shrinking labor force, and rising fiscal pressures. By 2064, the Maldives’ dependency ratio is projected to surpass 60, and by 2094, it is projected to surpass 80, underscoring the scale of the adjustment needed.

The urgency is clear. By the 2060s, the workforce will be declining just as pension and health demands are rising. Without rapid progress during the dividend years, the Maldives could be caught in a low-growth, high-burden trap.

Policy Priorities to Get Rich Before Getting Old

This demographic reality is not destiny. With clear economic targets, the Maldives can turn today’s favourable age structure into long-term resilience. To harness its demographic dividend before the window closes, the Maldives must pursue reforms that focus on human capital, productivity, the role of the state, and fiscal and social sustainability. The IMF stresses the same themes for aging Asia: raise labour force participation, boost productivity, reform pensions, and build fiscal buffers early. Korea and Singapore showed how these steps can turn a demographic window into lasting prosperity.

Unlocking Human Capital

Education and skills are the foundation of productivity. Stronger emphasis on languages (English and Dhivehi), mathematics, digital literacy, and vocational training will prepare Maldivians for sectors beyond tourism; while reskilling programs can help workers shift into other potential growth sectors such as logistics, ICT, and renewable energy. Preventive health care is equally important to keep the workforce productive. Raising female and youth participation is a priority: IMF research shows that higher female labour force participation is one of the most effective ways to offset demographic headwinds. Removing barriers such as childcare gaps, rigid work schedules, and weak school-to-work transitions can unlock this potential.

Reform the Role of the State

The Maldives suffers from an oversized public service and state-owned enterprises that employ too many people in low-productivity roles. This weakens private-sector competitiveness and strains public finances. The IMF cautions that bloated public payrolls crowd out growth-enhancing spending. The government’s role must shift toward enabling the private sector—through SOE reform, fiscal discipline, and policies that attract private investment in infrastructure and services. Right-size public employment and tighten SOE mandates to release talent to higher-productivity private roles and to free fiscal space for human capital and infrastructure.

Boost Productivity and Technology Adoption

Long-term growth depends on faster productivity gains. Experience across countries shows that innovation and openness are key to counteracting the effects of aging. The Maldives must accelerate technology adoption in tourism, logistics, and fisheries, supported by universal broadband, modern ports, and renewable energy. Policies that encourage entrepreneurship, ease access to finance, and support innovation hubs will create a stronger private sector ecosystem. To sustain growth, labour productivity should increase by no less than 2% annually (growth based on country experiences) through 2050—doubling output per worker within a generation.

Diversifying External Earnings

A narrow export base makes small states vulnerable. While tourism will remain central, the Maldives must move toward higher-value niches such as wellness and eco-tourism, while developing the blue economy—fisheries processing, aquaculture, and marine biotechnology. Digital services can open new markets beyond geography, positioning Maldivians in fintech, cybersecurity, and remote operations.

Securing Fiscal and Social Sustainability

The demographic dividend years provide a rare chance to build buffers. Public finances should prioritize education, health, and growth-enhancing infrastructure over wage bills and subsidies. Pension reform is urgent; delays will make adjustments more costly. Gradually raising retirement ages as the demographic dividend wanes, broadening pension coverage, and fostering private savings are essential to maintain solvency. Deeper capital markets and insurance systems can mobilize long-term savings, while fiscal rules and stabilization funds will protect against shocks and future aging costs. Bring public debt to sustainable levels consistent with resilience to shocks. Ensure pension solvency (including unfunded components as well) for at least 30 years through parametric reforms and funded pillars. Build fiscal buffers of 10–15% of GDP (stabilization and future-generations funds) before the dependency ratio peaks.

Managing Transition with Openness

The IMF highlights migration as one of the key tools available to small, aging economies to ease demographic pressures. Skills-based migration can fill labour gaps in construction, care, and specialized services, while diaspora engagement brings knowledge and capital. Policies should also support older workers staying active longer through phased retirement, second careers, and anti-discrimination measures.

Strengthening Institutions and Resilience

All of these priorities must rest on strong institutions. Predictable regulation, contract enforcement, and rule of law are essential for investment. Building climate and disaster resilience through instruments such as catastrophe bonds and green/blue finance will protect growth. Long-term planning that links demographic, fiscal, and climate policies is critical. Without strong governance, even good policies will fail in execution.

Taken together, these policy priorities point toward a future where the Maldives leverages its demographic dividend to build a productive, diversified, and resilient economy. The challenge is immense, but so is the opportunity. If the country can invest in its people, unleash its private sector, reform pensions, and strengthen its institutions now, it will not only get rich before getting old, but also age with dignity, stability, and prosperity.

Conclusion

The Maldives has a one-time opportunity in a century. Over the next 20–25 years, its demographic structure offers a powerful wind at its back. But that wind will reverse by the 2060s, when the population ages and begins to decline. The difference between success and stagnation lies in what is done now. Korea and Singapore show that prosperity is not destiny but the result of foresight and policy. If the Maldives invests in its people, technology, and institutions today, it can grow rich before growing old—and ensure that future generations inherit a resilient and prosperous nation.

Leave a Reply