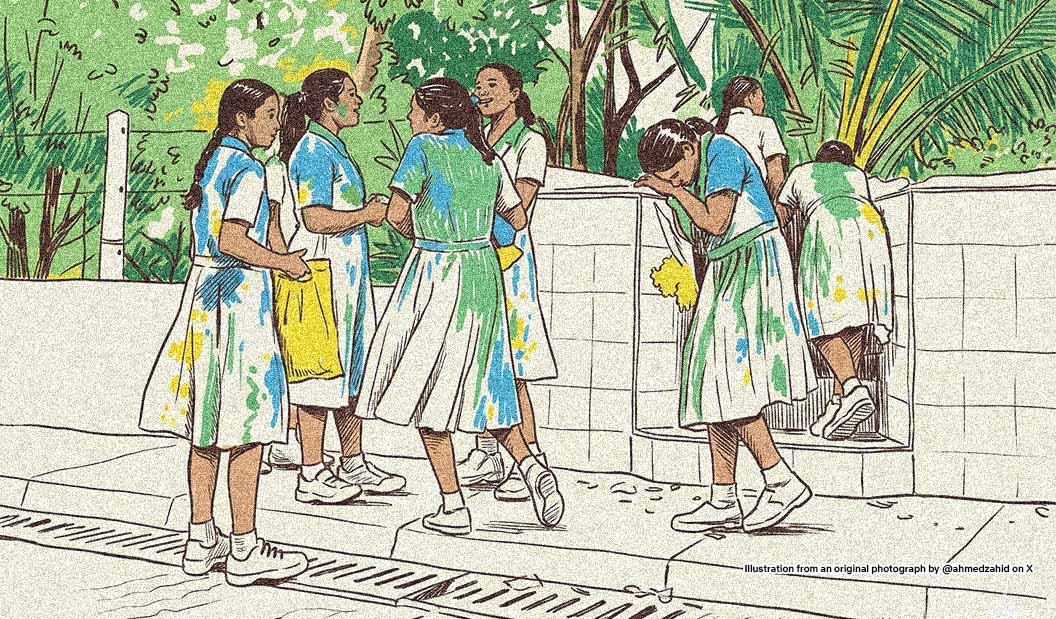

As we mark International Women’s Day 2025 a sobering assessment of the Maldivian reality reveals not just stagnation but even regression in the status of women here. Women are the most vulnerable and marginalised group in our communities, across the country, systematically disadvantaged across every measurable dimension of social, economic, and political life.

It is tempting to cite the years of progress, tempting to compare to regional countries. But our benchmark should not be measuring ourselves against who’s doing worse, nor against decades ago when we ourselves were doing worse. Instead, we must measure progress against our own national aspirations and commitments to gender equality.

The most recent Census Maldives and other national and regional studies lay bare the entrenched inequalities that persist. The evidence shows clearly, in the Maldives, for women, rights remain curtailed, equality remains distant, and empowerment remains elusive.

The Undeniable Evidence

This is not about perception or isolated anecdotes—it is about persistent, documented patterns of disadvantage: here are the facts, data we cannot ignore.

Violence persists with alarming ubiquity. One in three women aged 15-49 have experienced physical or sexual violence, whilst one in four partnered women endure intimate partner violence. More disturbing still, national prevalence data suggests that all Maldivian women experience some form of violence during their lifetime—making gender-based violence not an exception but a near-universal female experience.

Economic exclusion remains entrenched. Only 52.8% of women participate in the labour force compared to 88.7% of men. Maldivian women face a significant gender pay gap of 26%. Women in informal sectors face heightened vulnerability. The disproportionate burden of unpaid care work further constrains women’s economic opportunities. The message is clear: women’s economic contributions continue to be structurally squandered, devalued and restricted.

Political representation has deteriorated. Women now hold a mere 3.2% of parliamentary seats —a decline from the already abysmal 4.6% last elections. This places the Maldives among the lowest-ranking countries in South Asia for women’s political representation, making a mockery of claims about democratic progress or inclusive governance.

Justice remains inaccessible. An overwhelming 80% of women remain unaware of available legal aid services, whilst 59% report dissatisfaction with police responses. For women in remote islands, geographic isolation makes legal protection more theoretical than a practical right.

Youth opportunities systematically denied to girls: By age 35, women are six times more likely than men to be in NEET status (Not in Education, Employment or Training). In outer atolls, NEET rates for young women reach a staggering 42.7% compared to 11-12% for men, creating lifelong economic disadvantage.

Aging women face financial insecurity. Women constitute only 20% of retirement pension beneficiaries, reflecting their exclusion from formal employment and concentration in the informal sector. This creates severe financial vulnerability in later life, especially for women in the islands.

The Multiplication Effect: When Vulnerabilities Converge

The true depth of Maldivian women’s marginalisation becomes even more apparent when gender intersects with other vulnerabilities, creating not merely additive but intersectional, multiplicative disadvantages:

Geographic isolation intensifies exclusion. Women who remain in the islands face brutal labour market exclusion. Labour underutilisation sits at 26% compared to 18% in Malé, with informal sector employment reaching nearly 50% in atolls like Shaviyani (46.8%) and HDh (44.8%).

Disability compounds gender disadvantage. Disabled women’s labour force participation collapses to just 28% versus 34% for disabled men, with unemployment reaching 10% compared to 4% for disabled men. These disparities reveal how institutional structures systematically amplify vulnerability when gender and disability intersect.

Climate vulnerability follows gendered patterns. Though Maldivian-specific research is limited, climate change impacts are not gender-neutral, with women in rural and resource-dependent communities facing disproportionate consequences. The degradation of marine ecosystems here for instance, affects small-scale and subsistence fishers, relying on traditional fishing methods for their livelihoods. Maldivian women, who often engage in post-harvest processing and small-scale fish trading, face economic instability as fish stocks decline.

Public debt burden falls heaviest on women. Again, global experience consistently demonstrates that national debt disproportionately affect the most vulnerable first. In the Maldives, with the country’s external debt servicing projected to exceed $1 billion by 2026, resulting spending cuts will invariably disproportionately impact the marginalised and the poorer. For Maldivian women, these reductions represent not mere inconveniences but fundamental threats to wellbeing, security, and economic survival.

Accelerating Action: Breaking the Cycle of Systemic Inequality

The Maldives boasts progressive legislation and signaled commitment to international standards. On paper, we present well, but stark data reveals a different reality in practice.

Bridging this implementation gap is now an urgent national priority. We have a legal responsibility to ensure that every Maldivian woman and girl experiences the protections, opportunities, and rights already guaranteed in our laws.

Celebration is necessary – we should honour progress and women’s achievements. Yet we must also move beyond to address the disconnect between our commitments and lived realities. Only through committing to genuine implementation can we fulfill our responsibility to ALL women and girls across the Maldives.

Leave a Reply