On February 26, the Majlis passed an amendment to the Judicature Act, reducing the number of Supreme Court judges from seven to five. This development followed up with the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) of the Maldives suspending three Supreme Court justices just hours before a critical hearing on the new anti-defection laws. The latest development amidst opposition in the Maldives criticizing President Muizzu for damaging the country’s democracy and breaching the separation of powers. Although this is an issue related to Maldives’ domestic institutions and politics, it has a potential to strain India’s pragmatic outreach to the Maldives.

India’s Dilemmas:

Geography has largely determined the nature of India-Maldives ties. Owing to its proximity, India intends to foster mutual economic growth and development. It also fears that any external player or act of instability in the Maldives could have spillover implications. India thus plays a proactive role in the country through its multifaceted cooperation and development assistance but also exercises caution from being deemed as an overbearing neighbor. It recognises that it’s over-involvement in Maldives’ domestic politics could antagonize some sections of the polity and even trigger anti-Indian sentiments.

As a result, pragmatism has often taken precedence, and India has preferred working with the government of the day. Despite having great chemistry with certain political entities in the Maldives, India has attempted to work with different regimes, notwithstanding their overtly anti-India posturing. For instance, despite the controversial shift of power in 2012 – India eventually recognized President Waheed’s government and attempted to sustain a working relationship. Similarly, during the Presidency of Abdulla Yameen – India practiced caution, attempted to reconcile, and was slow to publicly criticize the government for stifling democracy. This was despite the then opposition – the MDP inviting the Indian government to intervene and uphold Maldives’ democracy.

However, when India’s interests and security concerns are at stake, it has taken a proactive stance. Such posture has been largely visible, especially in cases where India fears more political instability. For instance, in 2013 – fearing political instability and its spillover implications, India sheltered former President Nasheed and facilitated a deal that enabled him to walk free from a 13-year arrest warrant. Similarly, after multiple attempts at reconciling, India finally broke its silence in 2018 and criticized President Yameen for declaring an emergency. It also increased its diplomatic pressure against the government. Ties remained strained till Yameen was democratically ousted from power later that year.

Muizzu and India’s Pragmatism:

A similar dilemma confronted New Delhi when Mohamed Muizzu won the 2023 presidential elections riding on the waves of the anti-incumbency and “India Out” campaign. The campaign that alleged India to be an interventionist power, left the former with two options: one, to embrace pragmatism and engage with the new government, or to distance itself from the new government and provide more fuel to the anti-India fodder and ecosystem.

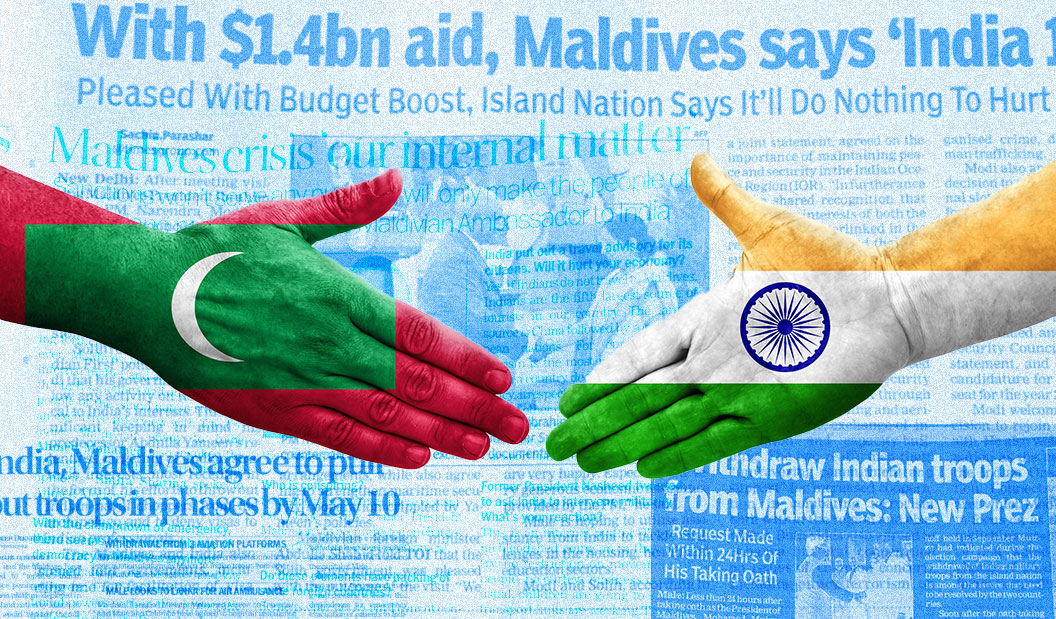

Delhi preferred the former over the latter, It began to pragmatically engage with the new government, rather than pushing it away. Despite being called a bully, India rolled over two treasury bills worth 50 million USD. Following this, a flurry of high-level engagements commenced from both sides, shaping a mutual vision for an Economic and Maritime Security partnership. This was followed by India pledging assistance worth 750 million USD (400 million USD and 30 billion INR) in the form of currency swaps. This is besides India’s budget assistance of 68 million USD and 45 million USD for 2025 and 2024 respectively. Recently, India also handed over defense equipment worth 4 million USD.

India’s pragmatic policy and assistance have many motives. It offers additional leverage to New Delhi to further its interests, mitigate the government’s anti-India posturing, and limit China from increasing its foothold in the country. It also emerges from a genuine desire to maintain and enhance historical and civilizational ties. There is also a concern that Maldives’ economy is in bad shape – with a consistently badly performing economy, ever-increasing debt burdens, and fast-depleting foreign reserves. Any economic mishap would thus have ripple effects on the country’s stability and create new internal and external security challenges for India, especially at a time when China is making inroads in the region.

Muizzu’s politics and the Indian prerogatives:

In return, the Muizzu government has somewhat been sensitive to Indian redlines. They have continued with certain Indian projects and maintained high-level engagements. The government has even moved certain Chinese projects that were detrimental to Indian interests. However, New Delhi is still worried about the government’s flirting and inclination towards Beijing. For instance, the recently implemented Maldives-China FTA has fiscal implications for Maldives. With media reports suggesting that Maldives’ revenues have declined after the FTA implementation, there seems to be genuine concerns in Delhi about the government’s policies, its implications for the economy, and their spillover implications for the region. As a result, India has hinted at revisiting its accommodative policy and assistance.

At the same time, President Muizzu’s politics is creating new pressure points on India. After securing a supermajority in the parliament, the ruling People’s National Congress (PNC) amended the constitution and introduced a new anti-defection law, which compelled MPs to toe the party line and leadership. When this amendment was challenged in the country’s top court, the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) suspended three judges dealing with the case. Delhi sees this as a domestic issue but is cautiously watching these developments. Increasing centralization of power, a troubled economy, and growing discontent against the government have never gone well with each other since the Maldives’ embraced multi-party system in 2008. This appears to be a perfect recipe for a perfect disaster.

History suggests that India’s Maldives policy is pragmatic, not unconditional. While India will continue to exercise restraint when commenting on several domestic developments, Muizzu’s Maldives faces two crucial challenges – a weakened economy and fragmenting politics. Any kind of potential instability, political or economic, will thus put more pressure on India’s pragmatic policy. In addition, the government’s close relations with China will continue to be a key determinant of India’s interests and policy. In this case, Delhi would have little options but to review these developments and revise its role and policies accordingly.

Aditya Gowdara Shivamurthy, Associate Fellow, Neighbourhood Studies, Observer Research Foundation, India.

Leave a Reply