“Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?” – Who will guard the guardians? Anyone, anywhere, working on anti-torture, on police reform, on judicial reform, on anti-corruption, press freedom, or hitting the streets in defiance of an autocrat, standing up for, claiming a right for, for oneself or for someone else, whether an individual or a group, a political party or an NGO, must be battling this interrogatory in their everyday bravery.

Today the world marks the International Access to Information Day. In the Maldives, this year also marks a decade since the enactment of our Right to Information (RTI) Act. This, therefore, is an opportune time to reflect on the RTI regime we have set in place, and how the regime is faring.

The democracy project here in the Maldives has been a cycle of one step forward, and two steps back. Democratic institutions have been found to be at the mercy of ruling parties and democratic principles falling victim to the whims of those in power.

The Right to Information (RTI) may not always capture public imagination as sensationally as other “political” issues such as human rights efforts and anti-corruption initiatives do. However, it is no less vital. Right to information is a vital mechanism as a custodian of democracy, transparency, accountability and good governance.

Freedom of information is an integral part of the fundamental right of freedom of expression, as expressed by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the right to information underpins all other rights. When it’s restricted, other fundamental rights and freedoms deteriorate.

The Maldives took a significant step towards transparency with the enactment of the Right to Information Act in 2014. This legislation was designed to empower citizens, providing them with the legal means to access information held by public authorities.

The Act establishes a robust framework for appeals, penalties, and safeguards, while preserving citizens’ constitutional rights to access information and knowledge. The scope of the Act encompasses all government bodies performing state duties, operating under the state budget, or receiving state funding. This includes the Executive branch, Parliament, independent commissions, political parties, and civil society groups. A recent Supreme Court ruling further cemented the mandate that these institutions adhere to the RTI Act.

Default Setting: Disclosure and Transparency

What we need is for disclosure and transparency to become the default setting for each state institution. The truly revolutionary step lies not in having the right RTI legislation, but in the state and its institutions recognising the right to information as the default in practice.

While the RTI Act appears comprehensive on paper, its practical application faces significant challenges. A Transparency Maldives study[1] from March 2024 said: “the implementation of crucial elements of the law still remains a huge challenge to this day.”

Developments over the last decade suggest a disquieting trend: RTI Commissioners since the enactment of the law, have consistently encountered resistance rather than compliance. Obtaining information remains a struggle for the public, which it shouldn’t be.

The disregard for, and even in some instances, the obstruction of the RTI Act by all the administrations since its inception, is insidious, but no less harmful for transparency and democratic governance in the Maldives.

Consequences of Neglecting Right to Information

The weakening of the RTI regime, whether a conscious onslaught, or through neglect, erodes fundamental democratic principles of transparency and accountability. It will create an environment where secrecy can slowly but steadily increase, undermining the foundations of democratic governance we are still trying to build.

Here are three crucial ways a weak RTI mechanism erodes democratic governance:

1. Thwarting public policy

We often view issues of transparency and accountability as “political” issues. But access to true and timely data is crucial for policy-making in all spheres; withholding crucial data will thwart evidence-based policy-making. For instance, limited access to comprehensive data on the following issues will hamper the effective policy-making required to address them:

a. Gender-based violence

b. Climate-change governance

c. Financial management

d. Child abuse

e. Illegal migration

f. Gang violence

g. Speeding

h. Cybercrime

i. Public health emergencies

j. Education system performance

k. Infrastructure development and urban planning

l. Small and medium enterprise (SME) development and support

For the Maldives to enact the right policies for long-term development, to remain on track to meet the SDGs, and to address its broader socioeconomic challenges, information, and citizens’ access to that information is crucial.

2. Reduced public trust and participation in governance

When a government shrouds itself in secrecy, and when citizens face obstacles in accessing information, their ability to participate meaningfully in governance is curtailed. This can lead to disengagement and apathy, and disengagement and apathy are fertile ground for authoritarianism to grow.

With secrecy, governments lose the trust of their citizens. The Maldives is currently on relatively stable political footing. However, we are on the brink of a financial crisis. As the government attempts to manoeuvre spending measures to manage debt, the government will require public trust. People will need to trust, for instance, why their government is cutting jobs, cutting subsidies, cutting infrastructure projects, changes to pensions etc. Public trust during a crisis is crucial for the people to believe the government will manage their finances responsibly for the long-term development of the Maldives.

Navigating an economic crisis without public trust in the government would set the stage for political, social and economic unrest.

Transparency in such a situation is therefore as beneficial for the government as it is for citizens.

3. Increased risk of corruption and mismanagement

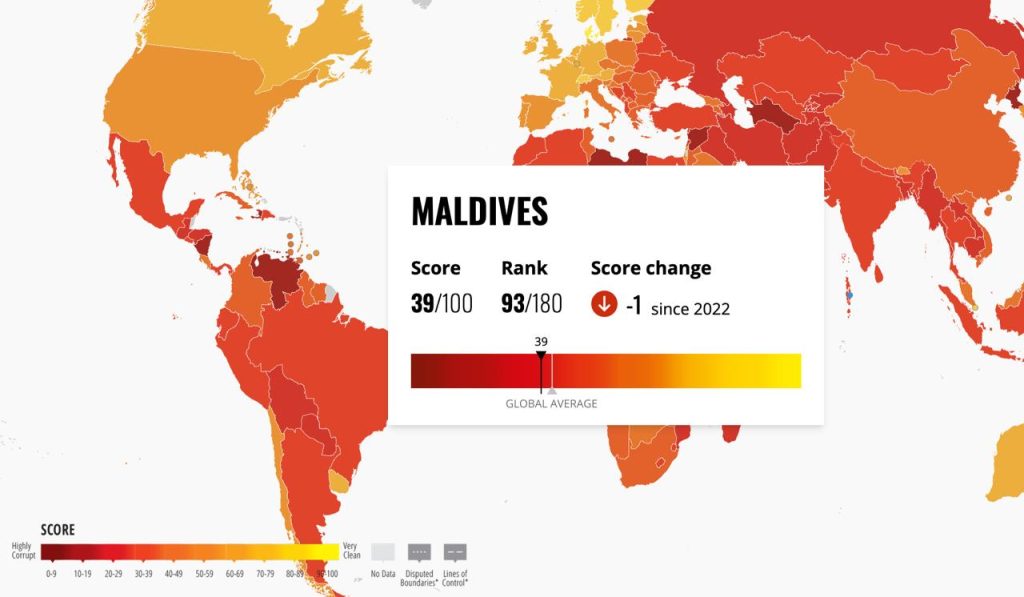

The Maldives has been sliding point by point on the global Corruption Perceptions Index, and a 2022 survey[2]by the International Republican Institute (IRI) showed corruption as the biggest concern among Maldivians. Both these findings illustrate that corruption is a real and pressing issue eating away at public trust, and underscores the need for robust RTI implementation.

Without effective RTI mechanisms, the risk of corruption and mismanagement grows.

The Ultimate Guardians: Us

Vigilance in democracy-monitoring is a responsibility that falls on all of us. We are the vanguards; the public, the media, civil society, the Parliament, political parties all have a responsibility to ensure our democratic institutions are standing firm, and we all have a responsibility to buttress when they falter.

Civil society organisations and the media have a crucial role in advocating for the RTI Act. They must continue to use the Act, challenge non-compliance, and educate the public about their right to information. Political parties and legislators, across the entire political spectrum, have an ongoing responsibility to uphold and strengthen this right, using all avenues at their disposal, such as parliamentary question time, petitioning the government, and proposing legislative amendments.

The successful implementation of the RTI Act ultimately depends on political will. Governments must demonstrate a genuine commitment to transparency by prioritising and fully supporting the Act’s implementation.

Reinforcing and Strengthening RTI for the Future

Reinforcing and Strengthening RTI for the Future The effectiveness of the RTI Act depends on a strong, independent Information Commissioner. Countries with robust RTI frameworks have Information Commissioners with significant powers to enforce compliance and penalise non-compliance. Recommendations include:

1. Strengthen enforcement powers

2. Clarify repercussions for non-compliance

3. Establish clear recourse for citizens when institutions fail to comply

4. Strengthen proactive disclosure mandate and mechanisms in order to reduce the need for individual RTI applications and increasing overall transparency.

a) establishing internal processes to automatically identify, prioritise, and publish information of significant public interest

b) developing and maintaining comprehensive digital platforms that regularly publish key information categories.

Maldivians aspire to a government that is open, accountable, and responsive to our needs. The unhindered right to timely and true information is integral to that goal. Sustained attention and effort are crucial now, before the erosion of this fundamental right becomes irreversible.

[1] https://transparency.mv/proactive-disclosures-by-public-authorities-a-review-of-compliance-to-the-obligations-under-the-right-to-information-act/

[2] https://www.iri.org/resources/national-survey-of-residents-of-the-republic-of-maldives–august-september-2022/