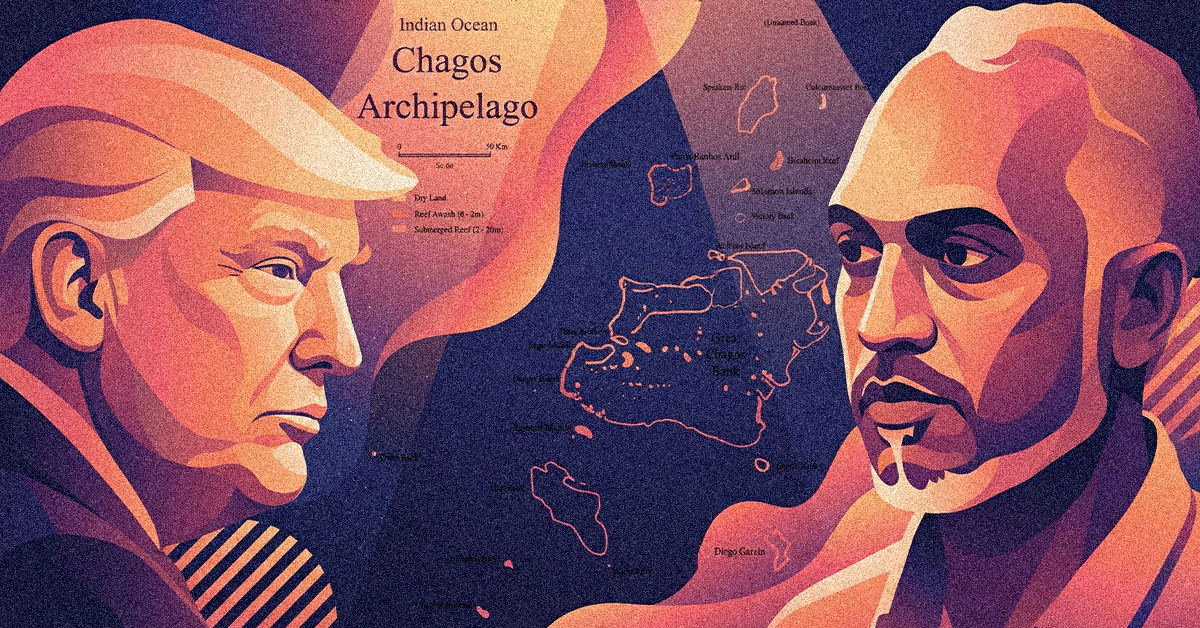

On 5 February 2026, President Mohamed Muizzu addressed the opening session of the People’s Majlis and declared that ‘not a single grain of sand from Maldivian soil, nor the smallest atom of its territory’ would be surrendered. He announced legal proceedings to recover maritime territory lost in the 2023 International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS)ruling, rejected the maritime boundary it drew, and asserted that the Maldives held the strongest claim to the Foalhavahi (Chagos) islands.[1]

Within hours, the Maldives National Defence Force began patrolling the disputed waters.[2]

The timing was deliberate. Two weeks earlier, President Trump had denounced the UK-Mauritius deal declaring that Britain was ‘planning to give away the Island of Diego Garcia, the site of a vital U.S. Military Base… FOR NO REASON WHATSOEVER.’[3] A crack had opened between great power allies over the Maldives’ own backyard, and Muizzu stepped into it.

He spoke to Newsweek and offered the USA an arrangement: sovereignty to the Maldives, continued US operations[4].

But his moment lasted one night. While Malé slept, London called Washington. It was 2am over the Indian Ocean, 9pm in Downing Street, 4pm in the White House. Prime Minister Starmer and President Trump had spoken, and the allies appeared to be back on track. Trump reneged on his earlier denunciation, and posted that the UK leader had made ‘the best deal he could make.’ Trump also added that he would never allow the base to be ‘undermined or threatened by fake claims or environmental nonsense,’ appearing to shut the Maldives out of the conversation entirely.[5]

Then, on 18 February, Trump reversed himself again. The deal was now a ‘big mistake,’ a ‘blight on our Great Ally.’ ‘DO NOT GIVE AWAY DIEGO GARCIA,’ he posted.[6] The crack has opened, closed, and opened again. The room for manoeuvre changes shape overnight. For a small state positioning itself in the spaces between great powers, reading the landscape well is everything.

Chagos is emotionally resonant in the Maldives. The geographic proximity is undeniable. The historical and cultural ties are real.Traditional Maldivian navigation coordinates record Foalhavahi by bearing alongside Addu, Maradhoo, Hithadhoo, and Kotte, as part of the Maldives. The ITLOS ruling carved away maritime territory, and the sting has not had time to settle into acceptance. There is live and unresolved debate in the country among academics, politicians, journalists, and the wider public on whether the Maldives was shortchanged, and the president is not alone in believing it was.

But the episode illuminates two things. The first is the limits of hedging: a small state positioned itself in the fractures between great powers without doing the groundwork. The second is the distance between statecraft and performance.

Muizzu inherited perhaps the most complex hedging landscape of any Maldivian president. Alliances that once seemed fixed are shifting beneath everyone’s feet. Traditional partnerships are being renegotiated or abandoned mid-sentence; even the largest powers are hedging. For a small state like the Maldives, the instinct to diversify is not just justified, it is essential and rational.

Muizzu has not stood still. His hedging has extended well beyond the India-China binary. With breathtaking speed, Turkey has gone from a marginal relationship to the Maldives’ most significant new defence partner. [7] It is the most significant boost to Maldivian military capacity in the country’s history[8], and it places Turkey in Indian Ocean waters in a way it has not operated in since the Ottoman Empire. The Gulf States are also coming in at a bewildering scale: Maldives has signed an 8.8 billion dollar deal, a figure exceeding the country’s entire GDP.[9] Such investments have transformed economies, and these are significant new partnerships. But hedging has its limits, and Muizzu has already discovered as much.

He came to office on “India Out” and ran headlong into fiscal reality. Public debt exceeding 125 per cent of GDP, over 1 billion dollars in debt servicing falling due this year, and the partner most able to provide immediate relief was precisely the one the campaign had promised to push away. But India’s stake is not charitable. The Maldives sits seventy nautical miles from Indian territory, and a new air corps, armed drones, and new billion dollar investments on its doorstep are not developments it will overlook.

There is also a question of method. The sentiment behind the Chagos claim is real, but the method was not. The method was performance, and the performance was unbacked by statecraft. There is no realistic mechanism by which the United States could hand sovereignty of Chagos to the Maldives. A rousing Majlis address, MNDF patrols, a bold interview in an American magazine: these alone cannot amount to stratecraft. It is a pattern in this administration, reading the room at home while misreading the room outside.

The Maldives has every right to pursue its own interests, chart its own partnerships, and must safeguard its autonomy. But a country that leverages its geostrategic location also bears a responsibility to the security and stability of the region it inhabits. And in waters this sensitive, you dip your toes first. You do not plunge. The Chagos bid was a plunge. Not a single country has backed it. Neither Delhi nor Beijing appeared to have been consulted. Not one of the new partners has said a word. Trump dismissed the claim without naming the Maldives. That is not a comfortable position for a small state to find itself in.

However real the sentiment, the Maldives cannot afford to disregard the multilateral frameworks it depends on and expect the world to rearrange itself accordingly. And as Muizzu has already learned, it cannot afford to keep surprising its partners either. The world order may be fluid, but the Maldives’ security depends on those frameworks holding and those partnerships enduring.

[1] President’s Office, Republic of Maldives. “Presidential Address at the Opening of the First Session of the Seventh Parliament of 2026.” 5 February 2026. https://presidency.gov.mv/Press/Article/36135 (accessed 14 February 2026).

[2] Ministry of Defence, Republic of Maldives (@MoDmv). “MNDF Begins Patrol of Disputed Waters.” X (formerly Twitter), 5 February 2026. https://x.com/MoDmv/status/2019364312515768829 (accessed 14 February 2026).

[3] “UK Defends Chagos Deal After Trump Calls It ‘Act of Great Stupidity.’” BBC News, 5 February 2026. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c0mkp021rvro (accessed 14 February 2026).

[4] Muizzu, Mohamed. Interview by Tom O’Connor. “Amid US-UK Clash Over Key Island Base, Maldives Leader Has a Deal for Trump.” Newsweek, 2 February 2026. https://www.newsweek.com/amid-us-uk-clash-over-key-island-base-maldives-leader-has-a-deal-for-trump-11444506 (accessed 14 February 2026).

[5] “Trump Rows Back His Criticism of UK’s Chagos Islands Deal.” Financial Times, 6 February 2026. https://www.ft.com/content/86e4d2f7-87b5-4f6b-98e6-1f6031527c6d (accessed 14 February 2026).

[6] Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump). “DO NOT GIVE AWAY DIEGO GARCIA.” Truth Social, 18 February 2026.

[7] Adhadhu. “MVR 560 Million Contract with Turkish Company for MNDF Military Drones.” 16 January 2024. https://adhadhu.com/article/48443 (accessed 1 February 2026).

[8]@ nex_def. “Turkey Gifts Doğan-class Fast Attack Craft to Maldives.” X (formerly Twitter), 2025. https://x.com/nex_def/status/1957729718528274910 (accessed 1 February 2026).

[9] “The Government of the Maldives and MBS Global Investments Pledge $8.8 Billion to Create the Maldives International Financial Centre.” PR Newswire, 4 May 2025. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/the-government-of-the-maldives-and-mbs-global-investments-pledge-8-8-billion-302445575.html (accessed 1 February 2026).

Leave a Reply