Not an Island Nation, an Ocean Nation

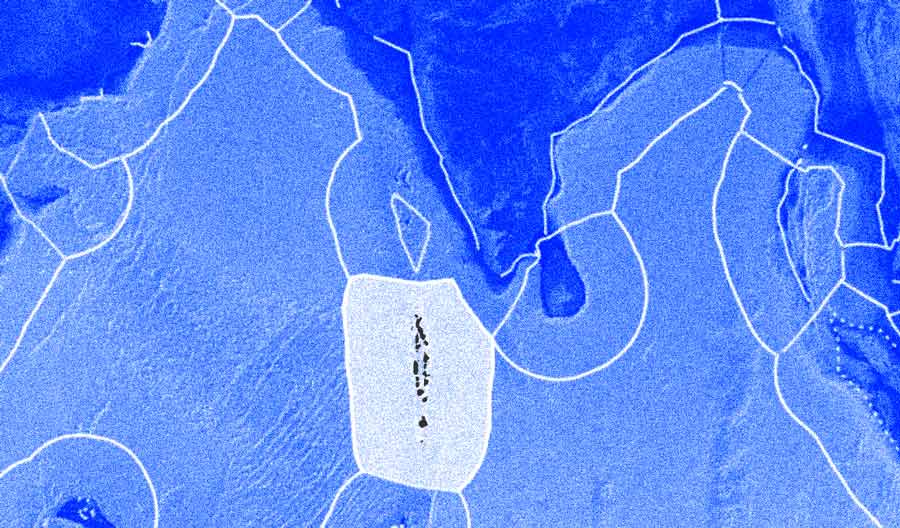

It might be shocking if I claimed that the Maldives is a larger country than the UK, Germany, Japan, Italy, and Norway. In fact, the Maldives is 2.5 times larger than the UK when one takes into account the ocean. The Exclusive Economic Zone of the Maldives amounts to 923,000 sqkm [1]. Let’s consider that the land we can stand on is just 1% of who we are.

For as long as we can remember, the Maldives has been referred to as a ‘small island nation’. Our development partners and donor agencies too continue to view us as fragile, dependent, and vulnerable. But that mindset has blinded us to our greatest strength. The truth is: we are not small.

We are a vast blue, ocean nation rich with potential, and splendidly wealthy with blue gold. Our sea is a living, breathing economy, teeming with life, energy, and opportunity. This policy vision calls on the Maldivian people to see the ocean not as scenery, but as our greatest national resource. We need to focus on building an economy that is not only more diverse but more inclusive, bringing real opportunities to youth, women, and communities in every atoll.

When we talk about economic diversification and seeking new avenues for growth, why must we look to how countries dependent on their land mass and riches from their soil achieve them? Why can’t we chart new routes – marine ones, more suitable for an ocean nation like the Maldives?

1. Diving into a Sea of Opportunity

One of the main reasons tourists travel all the way to the Maldives is experiencing the stunning beauty of our underwater gardens, rich in vibrant marine life. There are so many additional opportunities for our young divers who guide these tourists in their underwater adventures. They can be trained as marine scientists, conservationists, underwater engineers, and eco-tourism entrepreneurs. With state-supported certifications, diving becomes a lifelong profession.

2. Ocean-Based Pharmaceuticals and Cosmetics

Research across the world has found marine resources such as various types of algae and sea moss to be ‘magic ingredients’ for diverse purposes ranging from pharmaceuticals to skincare to ‘superfood’ supplements. Our coral reefs and marine species hold compounds that can be used in medicine, skincare, and biotech innovation[2].

A Marine Innovation Lab, backed by government and international partners, can help discover lifesaving treatments and commercial ingredients, turning marine biodiversity into national wealth.

3. Sustainable Seafood and Fish Farming

We have to think beyond limiting ourselves to tuna fisheries, which currently generates approximately USD120 million annually in exports[3]. While we have stuck with the tried and tested, the world has embraced a booming seafood industry valued at a staggering USD253 billion [4].

It is a tragedy that we rely on importing much of the seafood consumed in resorts when our waters could supply them fresh, locally. By investing in marine farming, such as sea cucumbers, oysters, lobsters, prawns, and clams, and modern fish farming, we create jobs in island communities, especially for women and youth. This supports nutrition, reduces imports, and opens global export markets.

4. Ocean Renewable Energy

Studies have been undertaken in the Maldives supported by Japan (NEDO) and India (NIOT) regarding Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC) as a renewable energy solution [5][6]. They confirmed that OTEC was suitable with thermal gradients ranging from 20 to 24 degrees Celsius at the surface and 4 to 6 degrees Celsius at depth, in southern atolls like Addu and Fuvahmulah. The Japanese study recommended floating OTEC plants using closed-cycle ammonia systems, and the Indian study suggested hybrid solar-OTEC models.

OTEC offers significant benefits, even over solar and wind energy, as it guarantees clean energy 24/7, with the added bonus of producing freshwater.

While there are some challenges to pursuing OTEC, such as high initial investment costs and limited deep-water access near some islands, this is still a very viable and preferable renewable energy model for the Maldives.

5. Geostrategic Shipping Advantage

Located at a key point in global sea routes, the Maldives can grow its own regional shipping liner to carry goods, as a hub that connects Africa to Asia. This means owning our trade, reducing freight costs, and developing port infrastructure in outer atolls. Over 200 ships cross the 8-degree channel daily. We can enhance our services to provide facilities to marine vessels from around the world passing through our seas.

Maldives State Shipping (MSS) was initiated with this vision in mind, and there is still much to aspire to, following MSS’s hopeful trajectory.

6. Aquatic Tourism Beyond Luxury Resorts

Blue tourism includes eco-diving, community-led excursions, marine heritage trails, and sea safaris run by locals. We must shift from an extractive resort model to a regenerative tourism approach that keeps income in island communities.

It is a key point to note that many of the research and study expeditions concerning our oceans are led by foreign agencies, often in partnership with resorts. A collaboration between schools, universities, and island communities could foster a rewarding enterprise, one that encourages our young people to reap the rewards of the ocean while also contributing to its protection and conservation.

7. Marine Conservation That Pays

Protecting seagrass and mangroves helps us earn blue carbon credits in global markets [7]. Coral restoration and marine parks can create jobs and attract research and grants. The Australian government’s investment in reef protection (including coral monitoring and restoration) helps sustain a $6 billion-a-year tourism economy that supports over 60,000 jobs [8]. In coastal Kenya, communities restored mangrove forests and began selling blue carbon credits on international markets, which generated income for local villages while protecting coastlines from erosion and improving fish nursery habitats [9]. There are numerous examples that show conservation is also smart economics.

Saving our Sea, Securing our Future

The Ocean–Conservation Connection: Economic expansion cannot come at the cost of the marine environment. The very resources that promise opportunity are under threat, from overfishing to plastic pollution and warming seas. Hence, all new ‘blue gold initiatives’ must be deeply rooted in conservation.

Some conservation-driven economic models can be:

- Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) that generate eco-tourism, research grants, and community management roles with proper plans and resources, ideally led by local councils.

- Coral farming and reef restoration enterprises, creating jobs while rebuilding habitats.

- Blue carbon credits: Protecting seagrass and mangroves can generate revenue through global carbon markets. A sustainably managed ocean is not just an ecological asset; it is an economic one.

- Community empowerment through ocean activities: Ocean-based diversification offers a chance to empower communities in outer atolls through women-led processing cooperatives, youth-led eco-tourism and dive ventures, and training in marine conservation and aquaculture.

Guardians of the Blue Gold

This is more than a development plan. It’s a change in mindset. We are not a poor, land-starved country. We are an ocean nation with wealth beneath our waves.

Let the future be blue, and ours.

References

[1] World Bank (2021). Exclusive Economic Zone Data.

[2] FAO. (2021). The global status of seaweed production, trade and utilization.

[3] Maldives Ministry of Fisheries (2022). Annual Fisheries Report.

[4] FAO (2023). Global Seafood Market Outlook.

[5] NEDO-Japan (2019). Feasibility Study on OTEC in the Maldives.

[6] NIOT-India (2020). Hybrid Solar-OTEC Potential in the Indian Ocean Region.

[7] UNEP (2022). Blue Carbon Credit Mechanisms.

[8] Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (2021). Economic Value of Reef Conservation.

[9] Mikoko Pamoja Project, Kenya (2020). Community-Led Mangrove Conservation and Carbon Credits.

Leave a Reply