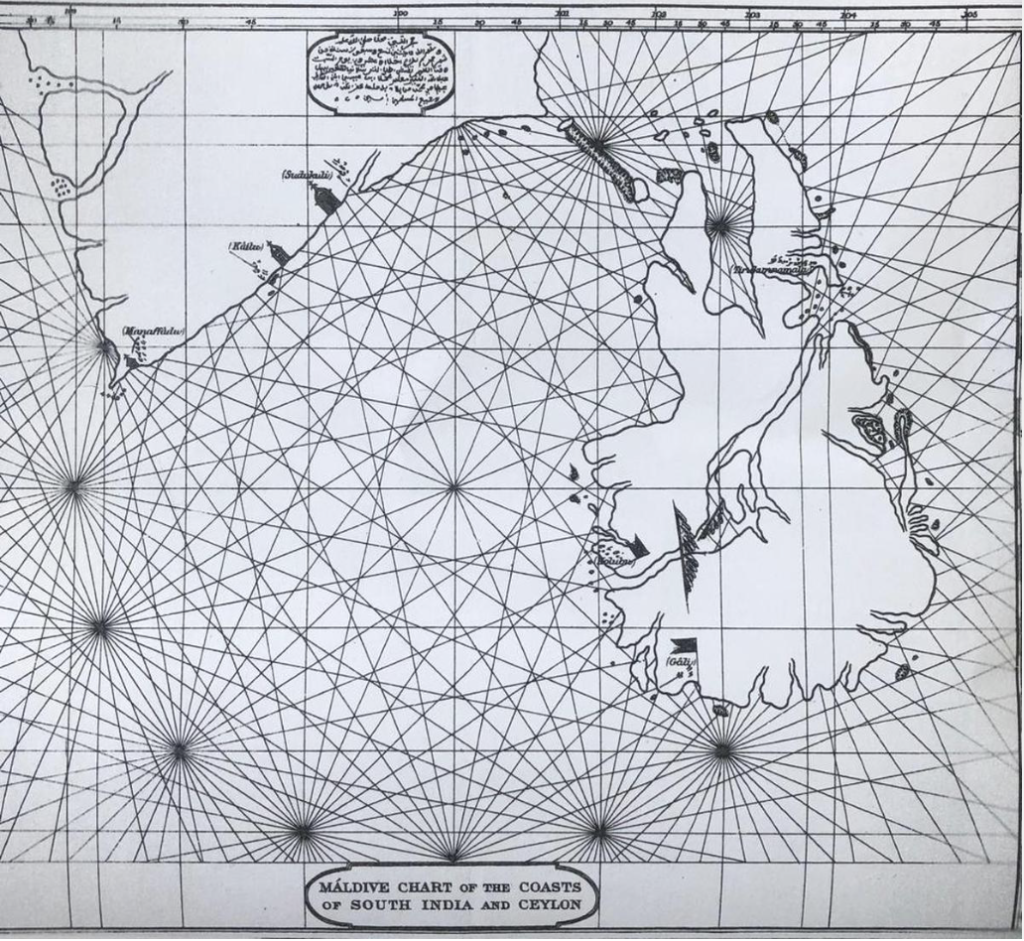

For centuries, Indian Ocean navigators, ship owners and merchants were the custodians of all the trade routes that crisscrossed their ocean. Ports and harbours on Bahr Faris (Arabian Gulf) and down to the Swahili Coast on the West and the ports and harbours on the far East to Malacca. Gujarat and Malabar Coast to Coromandel Coast to Bay of Bengal on the North and the Island States in the South of the Ocean. Hundreds of ports and thousands of families linked by navigation and trade, marriage, and love.

In the last one thousand years many emerging powers have frequently attempted to capture and centralise these Trade Routes, only to find that they finally end up dealing with the same merchant families of the Indian Ocean — families prospering in the Arabian Gulf, East Africa, Indian Peninsula, Bay of Bengal, Sri Lanka, Maldives, and other small island states.

Being a Battuta and a Sri Lanka fan, I have read Ibn Battuta in Sri Lanka. His Risala accounts of his travels in the Maldives and all throughout the Indian Ocean trading ports, is perhaps the best depiction of the port cities, types of vessels, cargo traded and merchant families of the Dhow Route’s early days. When Vasco da Gama was rounding the Cape of Good Hope, Chinese Commander Zheng He, a Muslim with 300 ships and 28,000 troops, was just leaving the Indian Ocean.

Portuguese rule immensely improved the boat building capabilities of the Indian Ocean port cities, but of course took away the trade from the local families. Dutch, East India Company and later the British Empire went on capturing and colonising the port cities. British colonial rule consolidated cargo in several bigger port cities. Britain’s advocacy of free trade also gave opportunity for the local traders to freely trade within the Indian Ocean states.

The resilience of the Indian Ocean rim ports and their hinterland is because of their smallness. Their small boats, Dhows, and Dhonis, increase and decreased in tonnage depending on the trade available. Their navigators were master mariners with expert knowledge of the winds, currents, reefs, and shallows of the seas. Their merchants had a vast network of connection and trade credit ties throughout the Indian Ocean ports. Their political connection and the ability to influence state policy was and still is comparable to no other lobby group.

China’s interests in the Indian Ocean grew in the context of the ‘One Belt, One Road’ initiative. The OBOR is comprised of two components: The Maritime Silk Road Initiative (MSRI) and the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB). It constitutes a massive geopolitical project that aims to construct built landscapes to enable flows of trade and investment by ‘promoting economic cooperation and connectivity’ between Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Europe.

The recent Chinese attempts to consolidate the Indian Ocean trade routes under The Belt and Road Initiative are yet to materialise. Meanwhile, the host countries of the Belt and Road ports have gone or are going bankrupt, defaulting on their sovereign debt. Sri Lanka has gone into default, East African port countries look shaky, and Pakistan stands on the brink of sovereign default. The Maldives is dancing on the blade’s edge.

Attempts to consolidate and centralise economic activities in hub ports remains a series of white elephants, dotted throughout the Indian Ocean rim countries, while the debt of the non-performing infrastructure breaks local economies and livelihoods.

There might be an argument for economies of scale and mega ports. This argument rarely holds water when robust small units with more flexibility and agility produce more inclusive and sustainable returns. Attempts to restructure the debt of the Indian Ocean port cities and proceed with the same mega infrastructure programs must not be the future vision of the Indian Ocean States.

In one form or another, the Indian Ocean states still maintain their maritime heritage. National and private shipping lines are plenty. Commodities to trade are in abundance. Ship type and wind and fuel hybrid propulsion can bring more efficiencies. Revitalising regional trade networks will be for the advantage of not only the port city economies in distress but also to maintain peace and stability in the Indian Ocean.

A form of this article first appeared on The Hindu.