Reef island and coastal area habitability in small islands is expected to decrease because of increased temperature, extreme sea levels and degradation of buffering ecosystems, which will increase human exposure to sea-related hazards[1]. These includes loss of marine and coastal biodiversity and ecosystem services; submergence of reef islands; loss of terrestrial biodiversity; water insecurity; destruction of settlements and infrastructure; degradation of health and well-being; economic decline and livelihood failure; and loss of cultural resources and heritage. The impacts of climate change on vulnerable low-lying and coastal areas can be considered ‘slow onset’ affects, in the long-term climate change presents serious threats to the ability of land to support human life and livelihood.

Reef islands and atolls are classified as primarily being composed of 80% calcareous rock, reef and unconsolidated sediments. These islands are typically low-lying and flat, surrounded by well-developed coral reefs that give rise to atoll structures. Due to their composition, the soil in these islands tend to be poorer, and from a human exposure standpoint, settlements’ face particular challenges such as coastal inundation by high tides, while fresh water remains scarce. Therefore, to protect against erosion and the rising sea-levels, hard sea defences are often required, and, in some cases, land reclamation is undertaken to accommodate growing populations[2].

Since the first inhabitants in 1500BC, the Maldives has thrived as a home to mighty seafarers and skilful fishers, as people of the Indian Ocean, a reef island archipelago of pristine white sandy beaches, vibrant turquoise lagoons, colourful coral reefs, and the vast blue ocean. The Maldivian people have thrived as a proud nation, with a unique identity, rich history, a distinctive culture, and language.

Today, intensifying hydrometeorological hazards, rising sea-levels, and the effects of climate change pose significant threats to our livelihood, our way of life and the very identity of our nation, to our very existence. Maldives remains amongst the most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, due to its low elevation, small size, dispersed geography, and exposure to multiple climate hazards such as sea-level rise, storm surges, coastal erosion, saltwater intrusion, coral bleaching, and ocean acidification.

Even though the emissions produced by Maldives is negligible (0.003%), the Maldives has legislated through the Climate Emergency Act (Act no. 09/2021), to achieve net-zero emissions by 2030, working towards climate mitigation. The country has also identified key adaptation strategies as part of the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)[3] in agriculture and food security, infrastructure resilience, public health, water security, coastal protection, coral reef biodiversity, tourism, fisheries, early warning systems, disaster management, and other cross-cutting issues. Though the NDCs speaks of improved spatial planning, NDCs failed to address potential long-term climate induced migration, specifically the potential population movement to safer, climate resilient settlements. The Maldives is already facing the consequences of extreme and slow onset events, a primary focus is needed for stronger and urgent adaptation actions.

Protecting our islands – cost of resilience

Maldives consists of 1,192 coral islands which form a chain of 82 km in length and 130 km in width, set in a territorial area of 859,000 sq. km. of Indian Ocean. Grouped into 26 coral atolls, most of the islands are quite small and low-lying, with an average elevation of 1.6m above mean sea-level. This unique small island geography makes these islands highly susceptible to the changing climate, sea level rise and other climate induced hazards, particularly affecting the coastline and natural island dynamics.

Human settlements, public institutions, and critical infrastructure are located too close to the shoreline and are already affected by sea level rise impacts, especially inundation, beach erosion, storm surges, and high waves. According to Shaig (2006), more than 42 percent of the population and 47 percent of all housing structures lie within 100 meters of the coastline. Human activities seriously increase the vulnerability of the nation, specifically through overcrowding of several islands, poor infrastructure, and depletion of beach vegetation. Several kinds of solutions have been implemented, from individual-level programs; voluntary migration, resettlement projects (mainly after the 2004 tsunami), and related land reclamation projects have been carried out, even though their contribution to increased resilience is disputable.[4]

Over the years several hard and soft engineering measures have been implemented in the Maldives. Hard engineered erosion and flood prevention measures include construction of armouring structures to prevent further retreat of existing beach line and wave overtopping include building seawalls, bulkheads and revetments. Shoreline stabilization measures have also been designed and implemented to modify coastal processes to achieve shore stabilization. The most used soft adaptation measures include beach replenishment, construction of groynes using sandbags, ad hoc seawall and ridges constructed from construction debris. Nature-based adaptation measures such as coastal vegetation retention and efforts for preservation of coral reefs are also implemented, though arguably in very few cases.

Hard Engineering

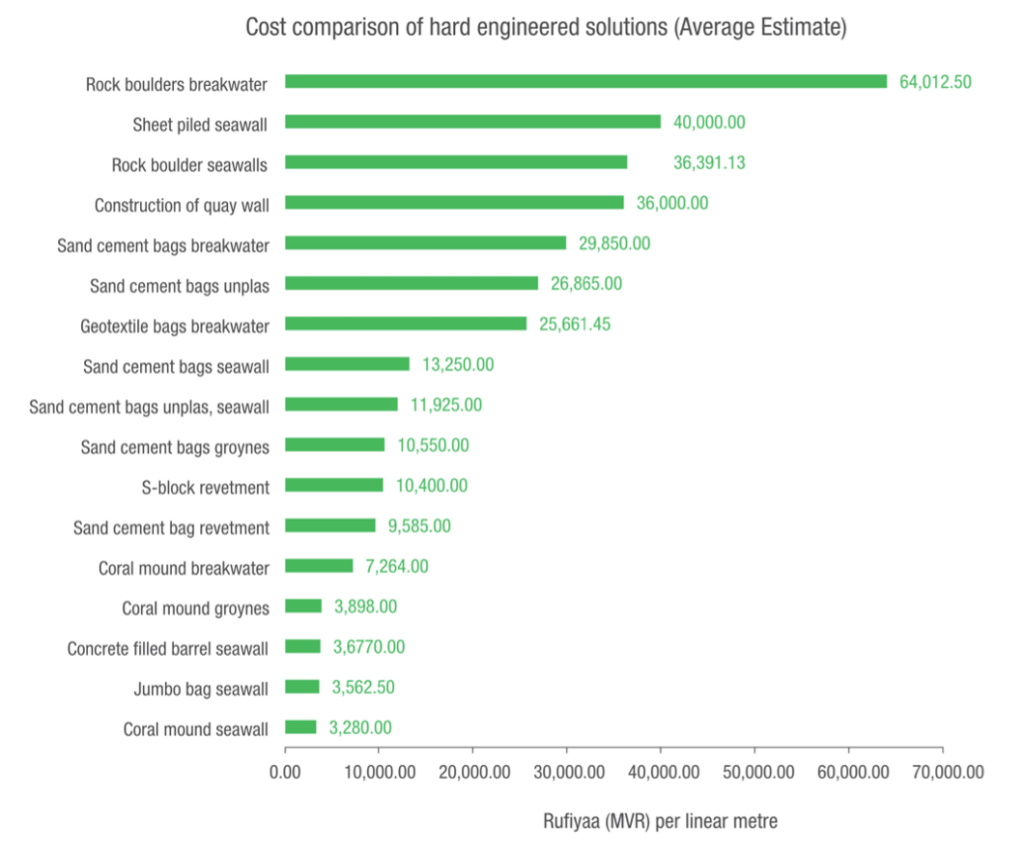

Concrete ‘tetra pods’ are the most expensive structures used in Maldives, at a cost of MVR64,000 per linear m (in 2011 prices). Other costly but durable options include sheet piles (MVR40,000 per m), armour rocks (MVR37,000) and concrete piles (MVR36,000). Efficient low-cost options such as sand filled geotextile bags (geo-bags) cost MVR26,000 per linear meter. The most commonly used sand-cement bag costs have increased to about MVR30,000 per m for a breakwater, a figure higher than geo-bags. Newly introduced revetments promise to be a much more cost-effective solution to high energy zones, particularly sand-cement bag type (MVR9,600 per m) and concrete Z-block type (MVR10,000 per m).[5]

Figure 1 Comparison of hard engineered adaptation measures, (Source: Survey of Climate Change Adaptation Measures, Ministry of Environment and Energy 2015.

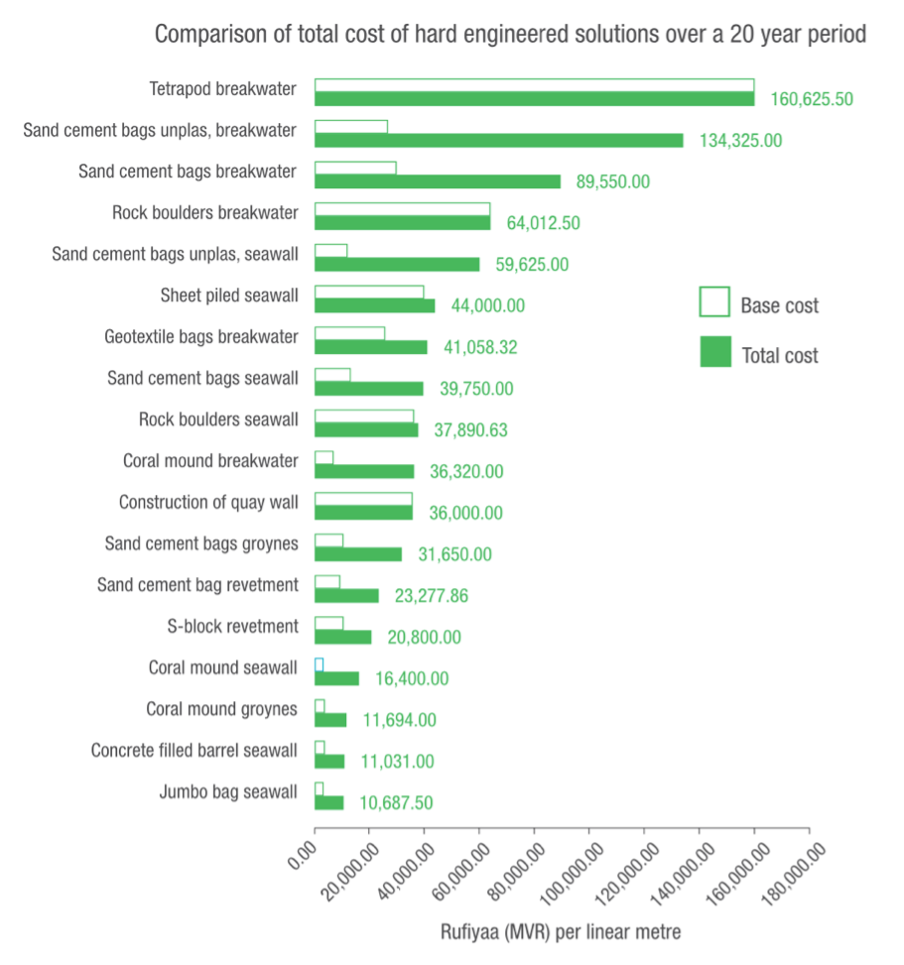

However, the real costs of such adaptation measures include maintenance costs over the designed lifetime of the project.

Figure 2 Comparison of total hard engineered adaptation measures over a 20-year period, (Source: Survey of Climate Change Adaptation Measures, Ministry of Environment and Energy 2015.

The estimated total cost of coastal protection of all inhabited islands and their entire shorelines ranges from US$524 million and US$8,779. This assumption excludes groynes, jumbo bags, coral mounds and concrete filled barrels since they are yet to be fully tested for their effectiveness against multi-hazards.[6]

The cost of protecting settlements only is significantly lower than protecting the entire coastline. Costs vary between US$329 million to US$5,506 million, a reduction of 37% from protecting the entire coastline of inhabited islands. These figures do not include costs of protecting resort islands as the use of extensive hard structures may not be an option for what is mainly considered as beach and reef tourism. Alternative measures are required for such islands.[7]

The costs of hard engineering measures vary and are linked to durability of construction and are generally more costly compared to soft engineering measures.

Soft engineering

When looking at soft engineering options, the costs of soft adaptation measures are less than hard engineering options. Upfront costs for various option vary within MVR 1,000 per linear m. Unlike most hard engineering options, maintenance costs are minimal for most soft engineering options. Amongst those surveyed in the study, beach replenishment involved the highest maintenance cost reaching MVR 4,875 per linear m over a 20-year period. This figure is still lower than the upfront costs of most hard engineering solutions. The costs of soft engineering measures can vary between locations, depending on site conditions and availability of suitable material such as sand, trees and healthy corals. Cost effectiveness is highly subjective as it depends on the perceptions of effectiveness. However, in general, the limited maintenance costs and nature’s role in enhancing the soft adaptation measures over time makes all soft adaptation measures highly cost effective in the long run.[8]

Nature-based solution and Ecosystem based adaptation, A race against time?

Small islands have focused increasingly on Ecosystem Based Adaptation (EbA) approaches and other Nature-Based Solutions that bring benefits both for the ecosystems and communities. Additionally, some islands are implementing climate-smart development plans such as improved management of existing and newly established protected areas, restoration of wetlands, urban forests/trees, sub-urban and peri-urban home gardens, and improved agroforestry practices towards increasing resilience to changing climate conditions, wildfires as well as decreasing food insecurity. Since the 1990s, artificial reefs have been increasingly used in small islands to support reef restoration and reduce beach erosion, especially in the Caribbean region (e.g., Dominican Republic, Antigua, Grand Cayman, Grenada) and Indian Ocean (Maldives, Mauritius). They have been more or less successful in reducing the destructive impacts from extreme events, depending on their technical characteristics and the local context.[9]

There is no doubt that EbA plays a significant role in mitigation, adaptation and resilience.

EbA approaches have many benefits but also face several challenges and limits. Biophysical limits can make some EbA and nature-based solutions ineffective: coral reefs are unlikelyto withstand increased temperatures, reducing the effectiveness of coral reef-based EbA options under higher temperature scenarios. Likewise, many other coastal and marine ecosystems, such as mangroves, face severe limitations with increasing sea levels and other climate impacts.[10]

In the long run, with what is being projected as a global climate catastrophe, small islands may not survive even with robust EbA measures.

Cost of resilience; what it comes down to:

While soft engineering and particularly EbA measures are cost effective and can increase the resilience of our islands, in the long run perhaps a mix of both hard engineering and EbA is the way forward for more sustainable resilience. The reality is that it is only ‘Resilience’ that Climate Change fears. For the Maldives, this means more climate finance and resilient development. The question is can we make it work for all our existing human settlements?

What is evident is that the cost for climate adaptation is not cheap. It’s important to note that the costs provided above are based on figures produced in 2015. Adding on the inflation, these figures would have significantly increased over the years.

Climate-induced migration

According to the UN, implications of extreme weather events have already caused an average of more than 20 million people to leave their homes and move to other areas within their own countries each year. In simple terms, these are people who are displaced or have had to migrate due to implications of climate change. The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) describes “Climate-related migration and displacement as one of the defining challenges they are seeing as a humanitarian network. It’s been seen across different regions and its manifesting in very different ways”.

For the Maldives, we may not yet feel the urgency to address the issue of potential “climate refugees”. Perhaps, because we have in one way or the other remained in our islands for millennia, we remain sceptical of the projections. Perhaps we as a people, are too optimistic and hopeful of our future. I for one remain hopeful. But the reality is that the slow creping disaster is not slowing down, and it will cause havoc.

Understanding the migration issue from an islanders’ perspective is essential. Arnall and Kothari (2014) reveal discrepancies among islanders regarding their attitudes to the link between climate change and migration. Their research shows that many ordinary Maldivians (non-elites) did not see sea level rise as a sufficient reason to migrate, should it occur in the near- to medium-term future as they believed they had other ways and means to adapt.

Arnall and Kothari (2014) point out that elites (experts) and non-elites report understanding the timescale of climate change—and related ideas of urgency and crisis—differently. Specifically, elites tend to focus on a distant future, which is generally abstracted from the reality of people’s everyday lives. Arnall and Kothari (2014) also identify a generation gap between older and younger populations discernible in relation to perceptions of any climate change–induced migration that might eventually occur. In general, older interviewees preferred to stay where they were but were also relatively open to the prospect of relocating, provided that the national government covered the full costs of resettlement. In contrast, many younger interviewees viewed climate change–induced migration as a potential opportunity to secure a better life elsewhere.[11]

A nation of migrants

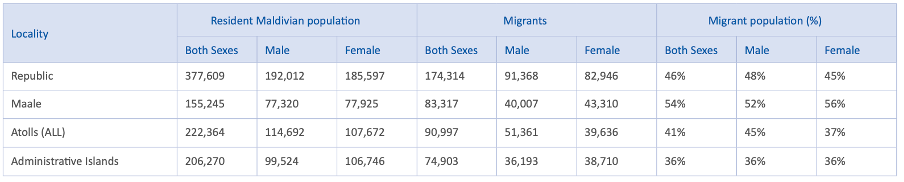

The 2022 census showed that close to half of the Maldivian population were internal migrants. The major migration stream in the Maldives is from the atolls to Male’. Internal migration is more towards Male’, where 41% of the population currently resides. On administrative islands, one in every 3 person was a migrant. Majority of the migrants fall within the working age-group.

Table 01: Migrants among Maldivians, 2022 (Source: Maldives Bureau of Statistics)

A significant proportion of migrants were in their late adult and elderly age and indicate the ageing of the migrants over time. This demographic shift suggests that individuals who migrated at a younger age may continue to reside in the place of migration, despite their reason for migration having been fulfilled.

At present, employment is the primary driver for migration, with one in every three migrants (34%) relocating for job opportunities. Subsequently, family migration (19%) and education (14%) constitute as the other main factors for recent migration. The proportion of individuals returning after completing their education is minimal now, at 4%, which was a notable decrease from 12% recorded seven years ago.

The story of internal migration in Maldives is very much tied to the story of development of the country. Development planning in the Maldives is not an easy undertaking. Especially due to the uniquely dispersed and fragmented small islands geography that makes the country. Years of unplanned, politically driven policy making on development has created a dependency towards Male’, the capital and centre of commerce and opportunities. Unfortunately, the inequalities remain obvious for a child born in an outer island compared that to a child born in Male’.

Decades of centralization and continued policy to create a “Mega” Greater Male’ Urban Settlement has led to greater inbound migration to the capital. The projections are alarming. The ‘Maldives Population projection 2014-2054’ estimates that close to 64% of the Maldives resident population will reside in Male’ by 2050.

A history of relocation and population consolidation

The presence of ruins on several currently uninhabited islands such as Gan in Huvadhu Atoll, shows relocations may have been part of people’s lives in the distant past. The exact reasons for abandoning these islands and possible relocations have not been established. However, one explanation is the onset of major epidemics or natural disasters. In the 1970s and earlier, regulations based on religious belief determined that a viable community should have minimum of 40 men, sufficient for a congregation for Juma Prayer performed on Fridays. During this era, some small communities owing to accidents at seas, and or high mortality rates experienced decreasing populations and consequently were compelled to move and join other communities. According to Maniku (1990), 13 island communities individually moved to new islands, after heavy destruction following a storm in 1918. This is an example of how disasters had in the past driven relocation in the Maldives.

Development-induced resettlements in the past were few and related to the development of an airport on the islands of Hulhule’ and the leasing of Addu-Gan (in around 1912) to build a British Royal Air Force base. In the first case, the people of Giraavaru-community had already experienced resettlement with their first forced movement in 1968 mainly as a result of regulations based on religious beliefs as mentioned earlier. It is noteworthy to recognise that the distinct and peculiar habits and culture of this community were not given due account for preservation when their relocations took place.[12]

The following table shows a list of islands that has been relocated in the Maldives from 1968 to 2018. These relocations were primarily driven by the government’s policy to move small populations to nearby islands, particularly in the 1990’s such decisions were made based on provision of essential services and as part of a national policy on population consolidation. Following the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami, several islands became uninhabitable, leaving many displaced. The Tsunami recovery and reconstruction efforts also led to relocation and integration of communities.

Table 02: Relocations from1968 to 2016 (Source: G. Gussmann & J. Hinkel, 2020[13])

| Year | Home Island | Destination Island |

| 1968 | K. Giraavaru | K. Hulhule’ *Later moved to Male’ for the development of the Airport. |

| 1968 | R. Ufulandhoo | R. Alifushi |

| 1968 | F. Himithi | F. Nilandhoo |

| 1968 | B. U’doodhoo | B. Eydhafushi |

| 1968 | B. Funadhoo | B. Eydhafushi |

| 1969 | B. Maahdoo | B. Eydhafushi |

| 1970 | AA. Kuramathi | AA. Rasdhoo |

| 1971 | Sh. Bomasdhoo | Sh. Farukolhu |

| 1992 | Sh. Tholhendhoo | Sh. Kendhikulhudhoo |

| 1995 | R. Ugulu | R. Hulhudhofaaru |

| 1995 | R. Gaaudoodhoo | R. Hulhudhofaaru |

| 1997 | Sh. Maakandoodhoo | Sh. Milandhoo |

| 1999 | Hdh. Hondaidhoo | Hdh. Nolhivaranfaru |

| 2006 | Hdh. Gemendhoo | Hdh. Kudahuvadhoo |

| 2006 | M. Madifushi | Adh. Maamigili |

| 2006 | Adh. Rinbudhoo | K. Thulusdhoo |

| 2006 | Sh. Noomaraa | Sh. Funadhoo |

| 2007 | HA. Berinmadhoo | HA. Hoarafushi |

| 2007 | Sh. Firunbaidhoo | Sh. Funadhoo |

| 2008 | HA. Hathifushi | HA. Hanimaadhoo |

| 2009 | R. Kandholhudhu | R. Dhuvaafaru |

| 2009 | Hdh. Faridhoo | Hdh. Nolhivaranfaru |

| 2009 | Hdh. Kunburudhoo | Hdh. Nolhivaranfaru |

| 2009 | Hdh. Maavaidhoo | Hdh. Nolhivaranfaru |

| 2010 | GA. Dhiyadhoo | GA. Gemanafushi |

| 2010 | L. Kalhaidhoo | L. Gan |

| 2012 | Hdh. Vaanee | Hdh. Kudahuvadhoo |

| 2014 | Lh. Maafilaafushi | HA. Hanimaadhoo |

| 2016 | L. Gadhoo | L. Fonadhoo |

Not all relocations have been a story of voluntary movement. Forced or “no-choice” movement has led to loss of intrinsic and inherent characteristics of some of these communities. Cultural and traditional loss as well as a sense of connectedness to their environment and ecosystem on which they depended on for their livelihood had not been accounted for and nor preserved or alternatives provided for them in their new host communities. Even today, there remains evident division and mistrust between the host and relocated communities.

According to the Ministry of National Planning, Housing and Infrastructure, the policy for involuntary migration was halted after the new Constitution of the Maldives was ratified in 2008. Relocations took place post-2008 as voluntary action from the whole community, through a consultative process; the entire migrant community unanimously agreed to move. For example, the island community from HA Hathifushi, was relocated due to impacts association with storm water flooding.[14]

Safer islands?

Over the years, particularly after the 2004 Tsunami, successive governments have either proposed or initiated concepts of “safer islands”.

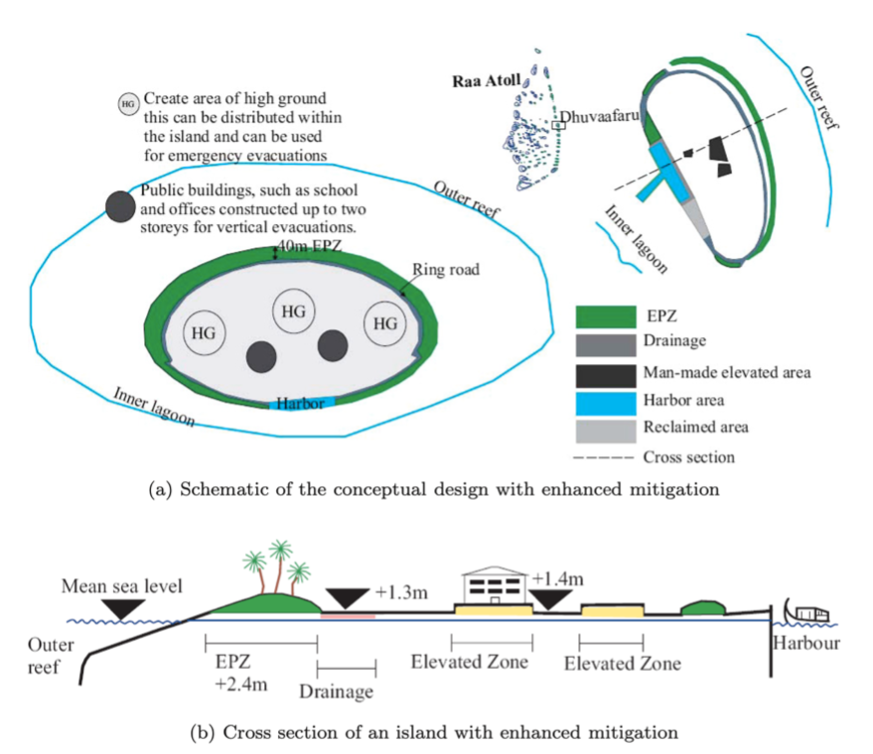

During the planning process of the rehabilitation and reconstruction works after the December 2004 Tsunami, major challenges were on how to make the islands safer and more resilient to tsunamis and the impending threat of sea-level rise due to climate change. In order to meet those challenges, the “safer island concept” was developed as an important adaptation strategy for climate change as well as tsunami’s. Some basic criteria have been developed for the selection of safe islands (1) easy access to an airport, (2) sufficient space and potential for reclamation and/or the possibility of connection to other islands, (3) viable economy and social services, and (4) sufficient space for subsequent population growth. The following main components and physical development characteristics of the islands are considered in the implementation of the “safer island concept” with enhanced mitigation measures:

(a) Environmental Protection Zone (EPZ): a high-level sand bund or embankment to protect the island from the high-rise sea level. This can be built using the sand material borrowed from harbour dredging. Salt and spray tolerant common coastal trees are planted in this zone.

(b) Lower drainage area: This area is located on the landward side between the ring road and the EPZ for the proper drainage of water.

(c) Elevated ground: compacted sand accumulations constructed higher than the ground level but lower than the EPZ. Community houses and various facilities are developed in this area. High buildings can be regarded as high ground for vertical evacuation.

After the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, the Government of Maldives decided to develop the following five islands as “safer islands”: R. Dhuvaafaru, A. Dh. Maamigili, Dh. Kudhuvadhoo, Th. Vilufushi, and L. Gan.[15]

Figure 3 The Safer Island Concept – Ministry of Planning and National Development, 2005

Generally, the term “safe islands” refers to Maldives’ larger islands, which will be better adapted to provide a safer environment and conditions for people who are threatened and forced to migrate as a result of natural disasters. The safer island strategy is focused on hard adaptation and structural engineering solutions, such as land reclamation and rising islands. The strategy, which is not new in Maldives but has changed across years and governments, is a controversial policy because it entails internal displacement and population consolidation. It has also been widely criticized for not fully considering environmental and other hazards. [16]

There have been multiple projects initiated by different administrations pushing forward on this agenda of creating “safer islands”. The current administration’s ambitious ‘Ras Malé’ reclamation project on Fushi Dhiggaru lagoon which have been declared as an undertaking that will be developed based on a zero-carbon and safe island concept. Other projects such as the “Building Climate Resilient Safer Islands in the Maldives (BCRSI)” – by the Green Climate Fund and JICA with funds of US$66 Million are ongoing.

According to the BCRSI project: The Government of Maldives continues to work on building “safer islands” with the aim of strengthening the long-term and sustainable resilience of Maldives Islands against climate change for enhancing economic development of the islands. The current policy is doing so while maintaining the sustainable link between the residents and the beaches. And by implementing appropriate management of coral reefs, and beach and coastal vegetation with physical measures at the coastal areas through combination of soft and hard components.

Where are we at?

Evidently, climate change poses an irreversible and existential threat to these islands, affecting islanders, their economy and their environment.

The resilience of Maldivian islands is deeply rooted on their natural bio-geophysical features, their size, shape, topography, vegetation, and their coastal and marine environment health. Unplanned, (unsustainable) development practices over the years have led to irreversible environmental change, increases in population pressures, unplanned urbanization, reclamation and coastal modification have significantly impacted these bio-geophysical features for the long run. Island topography, coastal dynamics, and geomorphology have all been altered, decreasing the natural adaptive capacity of our islands.

The cost of resilience; protecting our settlements sustainably for the long run or in other words “Climate-proofing” the Maldives is not cheap. Without a national dialogue, where communities and planners intentionally deliberate on a clear, long-term vision and strategy for climate adaptation and settlement resilience in the Maldives, the climate catastrophe will claim our shores, leaving generations of islanders homeless.

For the Maldives, climate-induced migration is inevitable. With the current data and projection, we know that sea level rise, storm surges and other coastal hazards are going to increase, causing significant damage to shorelines and infrastructure. What this equates to is certain forced relocations in the future. We also know that before permanent inundation can occur there would be many other impacts such as food security etc that may lead to islands becoming uninhabitable.

Maldivians have been migrating and they continue to do so for human development, in some cases voluntarily, but in most cases perhaps because there is no other option or choice. Even with decentralization rolling out in the country, there remains significant migration. No real change has yet materialized in service provision, access to critical facilities and infrastructure in most outer islands. Dependency continues to influence the decision for movement.

Relocations and development driven population consolidation is not a new concept in the Maldives. Over the decades, governments have made decisions that has led to relocation of entire communities, not all instances were voluntary, examples of forced relocation have proven loss of inherent rights and distinctive cultures of people. While it’s also important to note that development driven consolidation may have also increased living quality and standards for some.

Successive governments have also in some form or the other interpreted, proposed or implemented “safer islands” concept in the Maldives as an adaptation strategy for climate change as well as tsunami’s. This remains to be a key adaptation strategy to increase island resilience.

The cost implications for urgent and meaningful “total climate adaptation and resilience solution” for the entire population footprint of the country is too high to meet the current climate financing instruments accessible or available for the Maldives. There is an urgent need for a more meaningful and participatory decision-making process as a people in the Maldives to deliberate and agree on the future of human settlements in the Maldives.

Avoided national dialogue?

Questions such as “Can Maldivian’s sustain themselves with the implications of Climate Change in 187 islands?”, “Do we agree on the spatial planning direction towards a cluster-hub system?”, “Should we focus on increase connectivity to solve the issue of climate adaptation?”, “Should we live in 187 islands or maybe in 50 resilient ones?” and “Can we make all islands resilient?” needs deeper dialogue, consultation and research.

When I ask myself “why has this not been a major policy conversation in the Maldives?”, I am conflicted myself. I understand that it is the “islandness” of the islanders that makes these islands the Maldives. Relocation, consolidation and migration are not simple decisions. Consolidation, be it voluntary or forced will most certainly result in loss of islandness, distinctive heritage, culture, social ties and traditional livelihoods. Communities may even lose access to potential industries that sustain them (fishing, agriculture and tourism) that can create a form of economic displacement. Social resistance is understandable. These are perhaps reasons why this conversation is difficult and hard. But these difficult and hard conversations must happen, and it should start now.

An opportunity has perhaps presented itself. President Muizzu, following the Cabinet’s recommendation, has decided this September, to pursue the formulation of a 20-year National Development Masterplan for the Maldives. The President emphasised that the Masterplan would have legal backing, with a specifically designed law to support it. He further disclosed that “discussions at the island level, involving civil society groups, sports figures, political parties, and other respected individuals, would soon commence”.

[1] Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, Working Group II, IPCC Sixth Assessment Report

[2] Classification of small island types showing island characteristics and elements of human exposure, Kumar, L., Nunn, P. D., et al., (2018)

[3] NDCs embody efforts by each country to reduce national emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change. The Paris Agreement (Article 4, paragraph 2) requires each Party to prepare, communicate and maintain successive nationally determined contributions (NDCs) that it intends to achieve.

[4] Slow Onset Climate Change Impacts in Maldives and Population Movement from Islanders’ Perspective Brain. Robert Stojanov, Barbora Duží, Daniel Němec and David Procházka, Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD), April 2017

[5] Survey of Climate Change Adaptation Measures in Maldives, Integrating Climate Change Risks into Resilient Island Planning in the Maldives Project, Ministry of Environment and Energy, Maldives, 2015.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] IPCC Sixth Assessment Report Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, Chapter 15: Small Islands, IPCC 2022

[10] Ibid.

[11] Slow Onset Climate Change Impacts in Maldives and Population Movement from Islanders’ Perspective Brain. Robert Stojanov, Barbora Duží, Daniel Němec and David Procházka, Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD), April 2017

[12] An exploration of resettlement and its impact on social services: The case of the Maldives.

Ahmed Shareef Nafees – A dissertation submitted to the School of Development Studies of the University of East Anglia in part-fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, 2005

[13] What drives relocation policies in the Maldives? – G. Gussmann & J. Hinkel, Climatic Change (2020) 163:931–951 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-020-02919-8

[14] Climate Induced Migration in Maldives – Preliminary analysis and recommendations. Mareer Mohamed Husny, UNDP (2021).

[15] “Safer Island Concept” Developed After the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami: Case study of Maldives. Mahmood Riyaz and Kyung-Ho Park, School of Engineering and Technology, Asian Institute of Technology, 2009

[16] Slow Onset Climate Change Impacts in Maldives and Population Movement from Islanders’ Perspective Brain. Robert Stojanov, Barbora Duží, Daniel Němec and David Procházka, Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD), April 2017